Vilnius Travel Guide: An Introduction

A picture of Vilnius Old Town taken from the top of Gediminas Castle hill. Saint Johns' spire is the one visible the best. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Vilnius is the Lithuania's capital and its largest city (population 550 000). Officially established in the 14th century (but likely dating to an earlier era), this city is well-known for its massive UNESCO-inscribed Medieval old town. After all, Vilnius has been a capital since at least the 14th century. In that time, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania used to be the largest state in Europe.

Vilnius has been a multi-ethnic and multi-religious city for centuries, as evident in religious buildings of 9 different faiths, each of them pre-dating World War 1. Today that atmosphere still remains, with ethnic Lithuanians making less than 60% of the population (Poles – 19,4%, Russians – 14,43%, Belarussians – 4,19%).

Despite harboring many faiths and a remarkable religious tolerance, Vilnius always has been a religious city. It is said that you can see a church spire from any given site of its narrow Old Town streets. While not entirely true, the density of lavish baroque Catholic churches funded by the local wealthy families there is indeed one of the largest in Europe. Saint Peter and Paul church is famous for its 2000-statue interior while Saint Anne gothic church is known for its fine facade, supposedly loved by Napoleon Bonaparte. Four other Christian denominations, as well as Judaism and Karaism, also have their centuries-old houses of worship in Vilnius.

Alumnatas courtyard in the Old Town. Ranging from opulent to derelict, the courtyards of downtown Vilnius are a hidden face of the city. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

With its location in the heart of Europe (according to the French geographic institute, the center of Europe is in a certain well-marked spot north of Vilnius) Vilnius has been at the crossroads of many different armies and empires, Napoleon’s being just one of them.

The scars of the more recent occupations are felt better. You may visit the Parliament and Vilnius TV Tower where Russian soldiers killed 14 unarmed pro-independence civilians in January of 1991. Museum of Genocide Victims and Tuskulėnai memorial are located where Soviets used to torture, murder and secretly bury Lithuanians in 1940s-1980s (hundreds of thousands perished during that brutal occupation). Paneriai memorial marks the place where Nazi Germany killed a large share of Vilnius Jewish community during World War 2 (in 1931 Jews made up 27,8% of Vilnius inhabitants and the city is said to have been nicknamed the Jerusalem of the North).

Being a modern capital, Vilnius also has a new skyscraper district, centered around the Europos square. Moreover, the city is the best place in Lithuania for shopping, offering diverse opportunities such as Akropolis and Ozas shopping malls and the bazaar-like Gariūnai market. Together with Kaunas, it offers the widest array of museums: multiple art museums (both old art and modern art), the National museum and more. It is in Vilnius where there are the most cultural activities. It is here where the nightlife is the best in Lithuania.

More information:

Vilnius by borough (district): An area-by-area guide to Vilnius and its sights, with maps and pictures.

Vilnius by topic: Shopping, Entertainment, Churches and other topics of Vilnius.

Map of the Vilnius boroughs. The more interesting historical boroughs are color-coded and each has a separate article dedicated to it on this website. The Soviet boroughs area all painted in green shade. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Old Town of Vilnius (Senamiestis)

The UNESCO-inscribed old town of Vilnius is the heartland of the city. Its old palaces, narrow streets and countless churches of different faiths are what attracts tourists to Vilnius.

Katedros Square and the Castle hill area

The Gediminas Hill castle proudly standing above the Old Town (at the end of Pilies street in this picture). The red-brick tower is crowned by the most important flag in Lithuania. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The heart of Senamiestis is Gediminas hill which is crowned by the Upper Castle (14th-15th centuries). A single red tower has been rebuilt. It provides good skyline views of the city and also hosts a small museum.

At the bottom of the hill lies the Cathedral square with a white Neoclassical Vilnius Cathedral. The recently-rebuilt controversial Palace of the Grand Dukes is nearby, showing the original ruined basement and quite plain interiors, supposed to represent various ages (supplemented by the archeological finds and plaques on the Grand Duchy). The building evokes mixed opinions mainly due to its high costs and dubious cultural value. The Palace Arsenal (authentic) houses the National Museum, its halls providing a brief introduction to select features of Lithuanian history and culture. Once walled and more extensive, this complex used to be the heart of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Vilnius Cathedral is the most important church in Lithuania. A church in this place was likely established in 1251. The current façade dates to 1801 (architect Laurynas Stuoka-Gucevičius), but many of the side chapels are older. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The nearby green area consists of two separate parks: the Bernardine Garden and Kalnų (Hill) park. In the Hill Park, one may ascend the Three Crosses hill crowned by a sculpture of three crosses by Anton Wiwulski (1916), reminding of the Christian martyrs killed here by the Pagans in the 14th century. Demolished by the Soviets in the 1950s, the crosses were hastily rebuilt in 1989. Its symbol-of-Vilnius value was thus strengthened further.

To the south of Bernardine Garden stands the Saint Ann church, one of the most beautiful churches in Vilnius, as well as Saint Francis of Assisi church and St. Michael church (Baroque), now serving as a museum of religious art. Not far away is a large white Russian Orthodox cathedral – the center of Russian Orthodoxy in Lithuania.

The Old Town itself lies to the west of these religious buildings. It includes many other elaborate churches with the baroque style of 1600s-1700s being the most prevalent one. The Old Town is crisscrossed by narrow streets. Behind the buildings lie courtyards. A few of them still could be used as shortcuts to go from one street to another, but most are now closed off by the owners.

Rotušės Square and the Gate of Dawn area

Triangular Rotušės square with the white city hall building visible. In summer outdoor restaurants are opened here. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Another major square is the Rotušės square (City Hall square) where a former city hall stands (the two-floored towerless white building is humble by western standards). The domed Saint Casimir church and Saint Nicholas Orthodox Church are among the buildings surrounding the square.

To the north and west from here is the former Jewish ghetto. While the name "ghetto" may imply negative connotations, for centuries it was an ethnic district that had not been secluded from the rest of the city nor it was the only area where the local Jews lived (until the forced Nazi German relocation in the 1940s). Unfortunately, large chunks of Vilnius ghetto were demolished by the Soviets in order to make large squares and wide streets such as Vokiečių street. Vilnius Great Synagogue and most other Jewish religious buildings were demolished as well in the 1950s. The only synagogue still operating is further away in Pylimo street next to a former Jewish hospital. Pylimo street marks the border between Old Town and New Town.

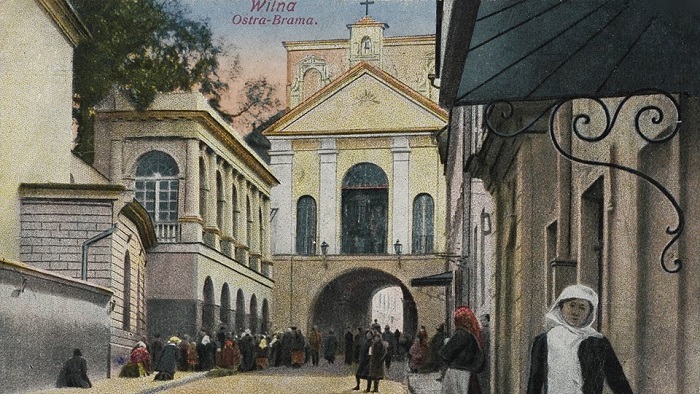

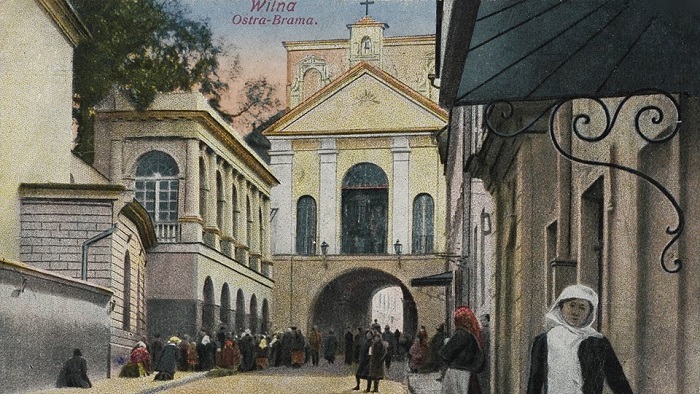

To the south of Rotušės square lies the Aušros Vartų street leading to the last remaining gate of the city: the Gate of Dawn, also a site for religious pilgrimage (a sacred miraculous painting of Virgin Mary adorns the gate and it is customary to make a sign of a cross when passing under). Next to the Gate, there are churches of three different Christian faiths: Russian Orthodox church and monastery of Holy Spirit, Roman Catholic church of Saint Theresa and Eastern Rite Catholic Church of Saint Trinity (an imposing gate leads to its monastery).

Gate of Dawn at the end of Aušros Vartų street. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Subačiaus street branches from Aušros vartų street. It passes the Artillery fortress. According to the myths, a basilisk used to live in nearby cellars. At the end of the Subačiaus street, there are two tall towers of the Missionary church not reopened since Soviet closure and the Holy Heart church that is closed as well. Beyond it, you may enjoy great skyline views of the city.

Pilies, Šv. Jono, Dominikonų and Trakų streets

Rotušės square and Cathedral square are connected by Pilies (Castle) pedestrian street which is beautiful but full of overpriced restaurants and souvenir vendors.

In Pilies street, there stands the university Church of Saint John the Baptist and Saint John the Evangelist. Behind its imposing white tower (for a long time the tallest building in Vilnius) lies the entire district occupied by Vilnius University. It claims to be the oldest continuously operating university in the Eastern Europe, teaching students in these same Renaissance courtyards since 1579 when it was established by Jesuits. Today, only three of the faculties (history, philosophy, and philology) are located here with the rest mostly transferred to a suburban campus in Saulėtekis (Antakalnis borough) in the 1970s. Vilnius University has ~23 000 students.

Vilnius University main campus. It has many courtyards which can be explored. Some marvelous interiors survive or have been newly crafted inside. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Šv. Jono, Dominikonų, and Trakų streets form a former road to Trakai city which was second in importance only to Vilnius until the 18th century. Now they lead to the New Town (Naujamiestis) borough and pass by several important Roman Catholic churches: the Shrine of the Divine Mercy with its miraculous altar painting that has a worldwide cult following, the Church of the Holy Spirit with its ornate Baroque interior and the spartan gothic Church of Virgin Mary Assumption, still hurt by Soviet desecration. The latter two are surrounded by partly abandoned buildings of closed monasteries.

At the place where Dominikonų street becomes Trakų street, this former thoroughfare crosses Vokiečių (see above) and Vilniaus streets. Vilniaus Street leads to Gedimino Avenue high street in Naujamiestis. Its most impressive building is probably the Baroque St.Catherine Church now used as a concert hall (well visible from Trakų/Vokiečių/Dominikonų/Vilniaus intersection). Vilniaus street is also an important nightlife hub.

Near the intersection of Trakų and Pylimo streets, the Old Towns gives way to the New Town (Naujamiestis). There, one may find the MO museum of modern art. Unlike most art museums in Lithuania, this one is privately managed and thus more concentrated on things such as marketing.

Užupis

Administratively part of the Old Town, Užupis is widely regarded to be a separate neighborhood. This 19th-century district beyond the river Vilnia is alongside the former road to Polotsk city (today in Belarus). Under the Soviet rule, many Užupis buildings were abandoned. After independence, the run-down district became popular with artists and referred to as the "Montmartre of Vilnius". The artists declared a micronation called the "Republic of Užupis" which celebrates an "independence day" coinciding with the April Fools Day. The half-humanist half-humourous constitution of the Republic is proudly attached to a wall in Paupio street (with translations into some 20 languages). Other publicity stunts include a Tibetan Square, occasional political posters and an alley known as "Jono Meko skersvėjis" (literally "Jonas Mekas crosswind", a pun on words "alley" and "crosswind", which sound similar in Lithuanian). Most buildings in Užupis are now repaired, but there are exceptions. The "Angel of Užupis" statue marks the central square and symbolizes the rebirth of the once-derelict district.

The main square of Užupis with the famous angel statue.

The Saint Bartholomew Roman Catholic church of Užupis offer masses in Polish and Belarusian. Not far away lie the early 19th century Bernardine cemetery, which is among the most beautiful in Vilnius.

See also: Churches of Vilnius Old Town.

Map of Senamiestis. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Naujamiestis (New Town) Borough in Vilnius

New Town is a product of 19th-century expansion which was minor in Vilnius comparing it to major metropolises of the Western Europe but nevertheless increased the Vilnius population fourfold (from 50 000 in 1800 to over 210 000 in 1914).

Naujamiestis was conceived by the Russian Empire to be the grand center of what was then the capital of its Vilnius Governorate and the main city in the Northwestern Krai (an administrative unit roughly comprising of modern-day Lithuania and Belarus). Naujamiestis lies entirely to the west of the Old Town.

Gedimino Avenue

2 kilometers long Gedimino Avenue (laid in the 19th century) is still widely regarded to be the main street of Vilnius. It leads from the Cathedral square to Žvėrynas borough passing by many stately buildings. Most of Lithuania's ministries, its government, and parliament, as well as its National Theatre, and three major courts of law, are located along this thoroughfare. Unfortunately, Gedimino Avenue is relatively narrow for its importance. Therefore, some of its architectural details might be hard to notice without looking upwards. Interesting buildings include (from east to west) the Science Academy building, Saint George Hotel (currently restored as an apartment building), Statistics department building, Court of Appeals building, Traders' Club building. The Bank of Lithuania also has a modern Money museum with Guinness-inscribed coin pyramid. Numerous restaurants and shops are primarily concentrated at the Cathedral side of the Avenue.

Gedimino Avenue near V. Kudirkos square during the Day of Street Music. Many events are organized in the Avenue and at these times it is pedestrianized. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

To the east of the Saint George Hotel, there is Vinco Kudirkos square (one-third way from the Cathedral to Žvėrynas) that boasts a statue to V. Kudirka (the author of Lithuanian anthem). It is surrounded by monumental buildings of every post-1880s style that was popular in Lithuania. To the north stands the Soviet functionalist Government of Lithuania (1982), east is dominated by the imposing historicist Gedimino 9 shopping mall (former municipality palace, 1893), west is covered by a Stalinist apartment building (1950s), whereas the southern flank of the square has interwar buildings (1930s) and a recently built Novotel hotel (2000s).

The Courts building (1890) at large Lukiškių square (about two-thirds of the way from Cathedral square to Žvėrynas) used to serve as HQ for both Gestapo and KGB. Many people were tortured and murdered here, some of their names now inscribed on the 19th-century building which now also houses an interesting Museum of Occupation and Resistance, also known as the Museum of Genocide Victims (where you can visit authentic KGB cells). Once a Lenin statue stood in the center of Lukiškių square and now this place is empty, but on the flanks of the square there are memorials for Lithuanian partisans and those exiled to Siberia by the Soviet regime. The particular Exiles monument was planned to be erected in Yakutsk, Russia, but this was banned by the Russian government even though accepted by city authorities.

The courts building in Gedimino Avenue and Lukiškų Square. Part of the building is dedicated to the Museum of the Occupation and Resistance. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Lukiškių square is surrounded by other interesting buildings such as the Church of Saints Phillip and Jacob (predating Naujamiestis, 1727) and a complex of terrace homes developed by banker Juozapas Montvila in 1911-1913; every part of the building is of different architectural style. One of the church towers hosts a carillon that offers free plays every day ~13:00 as well as before mass. Not far away is the 19th century Lukiškės prison, the nation's main penitentiary for over a century, now serving as an art space.

The Lithuanian parliament building on the western end of the Gedimino Avenue is modern (built in 1982, expanded in the 2000s). However, its historical importance far outweighs its size or beauty as it is the spot where the Soviet Union started to collapse when Lithuania became the first country to declare independence on March 11th, 1990. On January 1991 Soviet forces attacked Vilnius, but a great mass of people surrounded parliament and built concrete barricades (a couple of them remains as a monument on the Neris side of parliament still boasting the original graffiti). The Soviets did not capture the square, now named after independence (Nepriklausomybės). Laid over a major automobile tunnel, this square also houses the National Library and is overlooked by somewhat vacant office towers.

An example of the concrete barricades used during the siege of Vilnius in 1991 January. Graffiti tells a story of Lithuania's political climate of the time. Much of it is in English as the Lithuanians hoped to receive help from the West in their plight. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Bank of Neris

The southern bank of Neris at Žygimantų street (just to the west of the Cathedral Square) looks gracefully from the other side of the river. Buildings here are mostly early 20th-century apartment blocks and during this era, the street was a popular boulevard for leisure walks.

Naujamiestis remained the most important city borough up to 1990s. Therefore it has a fair share of interwar and Soviet monumental buildings. The best place to watch for Stalinist architecture is the banks of Neris river further downstream (Goštauto Street) where the House of Scientists stands crowned by a tower (1951). Here scientists used to live under the Soviet rule (some of them still do). Not far away to the east is the building dedicated for "returnees" - emigrant Lithuanians who chosen to return to Soviet Lithuania after Stalin's invitation the late 1940s. These returnees were important for propaganda but with the exception of apartments in this building Stalin gave them little else, breaking the promises.

House of the Scientists by architect Giovanni Rippa from Leningrad in Goštauto Street is one of the best examples of the monumental Stalinist architecture in Lithuania. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Between the Stalinist and the pre-War Neris banks stands a late-Soviet National Opera and Ballet theater (1974) with its kitsch interior decor. It is a good opportunity to see world-class opera and ballet performances at lower-than-in-the-West prices.

In front of the National Opera theater, you will see Žaliasis (Green) Bridge that leads to Šnipiškės borough. While a bridge over Neris river stood at this place for centuries, the current one dates to the Stalinist era (1952). It used to have the final Soviet statues in Vilnius on top but they were demolished in the late 2010s.

Tauras Hill area

Another nice 19th-century street is the uphill Basanavičiaus Street where the palatial HQ of Lithuanian railways (constructed in 1903 as HQ for railways of western Russian Empire) proudly stands. On the other side of the street is the Russian theater. This building used to be Polish theater before the Soviet occupation. It was built in 1913 following an architectural style reminiscent of southern Poland (Zakopane style).

Basanavičiaus-Mindaugo intersection. Railways HQ building is in the center. When built this 8 story building was the highest secular structure in the city. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Kalinausko street offers an alternative ascension route from the Old Town. It passes Frank Zappa statue unveiled by local fans amidst US media attention in 1995 (since 2010 its copy stands in Baltimore). It is not only a monument to the singer but also to the libertarian Lithuania of the 1990s when seemingly anything was possible with no bureaucracy to preclude it.

On the top of Tauras hill a Lutheran cemetery used to be but it was demolished by the Soviets. The hill gives nice views of the city.

The northern slope of Tauras hill is an open area. This allows great views towards Gedimino Avenue, Neris river, and New City Center. If you go downhill by stairs from here you will reach Pamėnkalnio street. Running parallel to the Gedimino Avenue Pamėnkalnio street also has some nice buildings from the 19th century and the Stalinist era Pergalė cinema (now a major casino). Pamėnkalnis, by the way, is the historical name for Tauras hill, possibly relating to ghosts.

On top of the Tauras hill a calm M. K. Čiurlionio street passes by turn-of-the-century urban villas, Vilnius university faculties, and new expensive developments. It leads to Vingis (Bend of Neris) park, a popular place for summer strolls and an unlikely location of the Lithuania's main rugby stadium in addition to the German soldier cemetery and the central lawn where the pro-independence demonstrations of the late 1980s have now been replaced by the gigs of foreign divas.

Station district

Both railroad station and bus station of Vilnius are located in the southernmost end of Naujamiestis. Together with the surrounding plaza, they were built under Soviet occupation (after destroying many older buildings). But the adjoining streets like Šopeno are still full of stately buildings dating to the dawn of the 20th century and are worth exploring. Additionally many cheap hostels and various restaurants are located within easy reach from the stations. This particular area known as „Stoties rajonas“ („Station district“) has a bad reputation for prostitution and criminal activity but it has been undergoing a rapid gentrification and "hipsterization" in the 2010s, offering numerous popular bars.

Map of Naujamiestis. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Šnipiškės Borough in Vilnius

Sometimes Šnipiškės is regarded as a "Village inside a city" and its central districts still live up to this title. They are almost entirely dominated by wooden private homes. Most of them are heated by burning wood in stoves and many even lack tap water and sewerage (public water outlets are used). Some of the streets are not yet paved. This central Šnipiškės is an indirect heritage of Soviet urban planning when new districts would be built in some places while some others would be left completely untouched. Šnipiškės was among the later and so you can still witness how a 19th-century wooden suburb of Vilnius looked like. Streets like Giedraičių or unpaved Šilutės are the best to see this.

Central Šnipiškės is no Žvėrynas. Despite being in a walking distance to the city center, this district somehow fails to attract the rich and remains dominated by its old inhabitants.

19th and early 20th century wooden houses in Giedraičių street, Šnipiškės. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The southern Šnipiškės is a different story, however. Designated to be the "new center of Vilnius" in the 1980s, it saw its old homes replaced by 22 story Hotel Lietuva, planetarium and the largest department store in Soviet Vilnius. In the 2000s, the independent Lithuania continued this trend, with the first skyscraper district in Lithuania hugging the modern Konstitucijos (Constitution) Avenue and the new Europos (Europe) Square. Several mid-sized shopping malls and many offices are located here next to Neris river as is the National Gallery of (20th Century) Art. On the area's western edge the Baltic Way memorial commemorates the world's original (and largest) human chain (2 million people, 650 km for the Baltic States independence in 1989). The tricolor wall itself is unique for being crowd-funded, every brick bearing a name of a benefactor.

The pro-development stance that regards the wooden Šnipiškės as a total anachronism frequently clashed with a stance that sees it as an important heritage that must be saved. There was a time when the owners of some old wooden houses would burn them down in order to get a construction permit for a modern building. However, as of now, it is still possible to see a remarkable contrast between a 19th-century suburb and 21st-century city center within meters from each other in Šnipiškės. They are nearby but not intermingled as there is a very fine invisible line that divides the glass-and-concrete skyscrapers on the one side, and the World War 1 era buildings on the other.

A view south from Central Šnipiškės (Giedraičių Street) with the new city center visible. The circular skyscraper to the right is the 33 floor Europa Tower. With 148 meters height, it is the tallest building in the Baltic States. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The main thoroughfare of Šnipiškės is the north-south Kalvarijų street. You see all the faces of Šnipiškės by traveling it and you may always turn westwards into the side-streets. Kalvarijų Street begins in the south with graceful Saint Raphael church and monastery (1709) on one side and a nice Gothic revival palace on the other, sadly half-destroyed by the Soviets. These elaborate buildings could as well be in the New Town which is just beyond the Žaliasis bridge.

Going the Kalvarijų street northwards you pass the recent developments and then wooden buildings start appearing. One of the largest marketplaces in Vilnius (Kalvarijų turgus) and a Russian Orthodox church of Archangel Michael are located alongside.

Kalvarijų street serves as a trunk road linking city center to its northern boroughs. Therefore many buildings here have been converted to commercial use. If you want a more authentic experience, you may choose to stroll in some of the parallel streets such as Giedraičių and Šilutės.

There is a third and the least interesting face of Šnipiškės: the north of the district (to the north of Žalgirio street). It is dominated by Soviet functionalist apartment blocks that are not different from similar buildings elsewhere in Vilnius (except that there is an occasional wooden house left standing between the new apartment blocks).

Map of central and southern Šnipiškės. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Žvėrynas Borough in Vilnius

Žvėrynas name means "Land of the Beasts" and reminds of a time when this forest inside the bend of Neris river was the hunting ground of the nobility. By the early 20th century, however, it was built up as a wooden suburb. Many of its wooden houses have elaborate architectural details that made this district famous. Most of the homes here are still detached private houses owned by a single or several families.

An interesection of Kęstučio and Moniuškos streets. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

In the 1990s, Žvėrynas became a prestigious neighborhood. It is within a very easy reach from all main districts of Vilnius and yet next to the greenery of Vingis park. Moreover, its tree-lined streets are never overcrowded. Therefore, many new multistory apartment buildings were built while numerous old houses were repaired. This is in stark contrast to Šnipiškės where many wooden homes still stand in a sorry state.

Žvėrynas still has its old charm, however, and a stroll around its parallel streets is definitely rewarding. Here you can see the only Karaite Kenessa of Vilnius (and one of two in Lithuania; 1923), two Russian Orthodox churches (the larger one, known as Znamenskaya, was built by the Russians in 1903 to counterweight urbanistic importance of the Catholic Cathedral at the opposite end of Gedimino Avenue) and a towerless Roman Catholic church (1925). Its interior has been decorated clandestinely while under the Soviet occupation by self-taught artists in both religious symbols and images of Vilnius. The iron-arch Žvėrynas bridge, which joined then-suburb to the city in 1906, is also still standing.

Karaite kenessa in Liubarto street is one of only two remaining Karaite religious buildings in Lithuania. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

But these buildings may only serve as a pretext for your explorations as it is likely that you will find some of the ordinary houses that line the side-streets to be even more compelling.

Several embassies are located in the calmness of Žvėrynas.

Map of Žvėrynas with places of interest marked. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Antakalnis Borough in Vilnius

A former Antakalnis suburb of Vilnius is lined along a single street that starts near Cathedral Square and goes northwards parallel to river Neris. Its most interesting sight is definitely the white Baroque interior of the Saints Peter and Paul church (construction began in 1668), which is one of the wonders of entire Lithuania.

A detail of Saint Peter and Paul church interior with only a small fraction of its 2000 meticulously shaped white figures and reliefs. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Not far away from this church, there are several palaces built by the nobility and businessmen of years gone by. Some of them well visible from the main street (like that of Vileišiai), others, like that of Sluškos (now Academy of Theater and Music), are hidden behind other buildings.

The architecture of southern Antakalnis is very eclectic with buildings from very different eras standing side-by-side. Saints Peter and Paul church, as well as the Sapiega manor, are a heritage of the 17th century. Sapiega palace has been resored while the single-story buildings in its extensive park (now reduced in size) have been reused by a hospital and then transformed into a startup hub. You may walk around freely in its area. The Church of the Saviour is small but it has a pretty interior.

Many detached private homes of Antakalnis dates to the 19th century or the early 20th century. This includes the elaborate yet compact Vileišiai palace of 1906 (an era when businessmen rather than nobility were building the most impressive residences). Vileišiai family were industrialists notable for promoting Lithuanian language at the time when most of the city‘s elite preferred Polish.

Vileišiai Palace is small in size but not in elaborate details on its façade. The palace is surrounded by larger buildings that were also owned by the Vileišiai businessmen family. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The development of Antakalnis continued in the interwar period when a district of modern white terrace homes was added in front of the Saints Peter and Paul church. The borough was further extended by the Soviets who built many blank apartment blocks amidst Antakalnis‘s older manors and wooden homes. The expansion continues as some new buildings have been constructed in southern Antakalnis since the 1990s.

Surrounded by Soviet buildings is St. Faustina home, a former nunnery where sister Faustina received the visions that served as a basis for the world-famous Divine Mercy painting. Now it is a minimalist museum of relics, 1930s Vilnius images, and a religious shop.

The northern part of Antakalnio street (north of the Sapiega palace) is mostly built up by Soviet buildings. At the northernmost end, there is the Saulėtekis district that serves as a pan-university campus. Main campuses of Vilnius University, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University are located here. 16 stories tall student dormitories, nicknamed "New York" by those who live there, dominate the scene. Unless you study here there is little to see as the campus is built in the 1960s or later. Modern University library is, however, a pleasant exception: free-to-use and open 24/7 its 4 story reading rooms houses thousands of English books including some travel literature (night-time entry restricted to members).

Vilnius University library (completed in 2013). ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Two cemeteries crown the forested hills east of Antakalnis. Antakalnis cemetery serves as the national pantheon for Lithuania's artists, politicians as well as multi-national soldiers and victims of war: the members of ill-fated Napoleon‘s Grande-Armee, the Polish troops of 1919-1920 and those killed by the Soviet invaders in 1991. Nearby picturesque Saulės (St. Peter and Paul) cemetery is much older (19th century), providing a final resting place for the pre-war nobility and ordinary citizens alike.

Map of the southern Antakalnis. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Žirmūnai borough

Žirmūnai is a largely rebuilt borough that has some hidden gems.

Foremost among them is the Tuskulėnai Peace Park. Once a manor owned by Tiškevičiai and Valavičiai families (built in 1825) it was nationalized by the Soviets and used to dispose the bodies of political prisoners. At least 724 were buried here, including Lithuanian freedom fighters, priests, and Polish Armija Krajowa fighters. Some criminals (10%) were also buried but, as Soviets purposefully damaged all the bodies with acid, the bones were impossible to distinguish after exhumation in 1996.

Neoclassical Tuskulėnai manor now houses park offices and temporary exhibitions while a small but modern museum is located at the southern end of the complex. The underground memorial and columbarium (2006) look like a crowned burial mound in the center. Its massive brutalist entrance hides an impressive post-modern interior, incorporating Egyptian and vernacular Lithuanian details. A visit could be arranged at the park offices or museum.

Interior of Tuskulėnai Memorial. The symbolic round central room (right) is surrounded by a corridor full of numbered urns with the remains of Tuskulėnai victims. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The Soviet brutalist Palace of Concerts and Sports (1971) on the northern bank of Neris river is built on a place where Vilnius largest Jewish cemetery once stood (until it had been destroyed by the Soviets in the 1950s). With the completion of new arenas, this one is no longer used. The car park in front of it was turned into a grassland for memorial purposes in the 2000s.

Palace of Concerts and Sports in Vilnius (Olimpiečių Street) is an example of what the key public buildings of the late Soviet era looked like. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Formerly the complex also included the Žalgiris stadium, built by the German POWs in 1948 and the largest stadium in Lithuania, a red-brick ice rink, and a Stalinist Žalgiris swimming pool. However, all these buildings have since been demolished to vacate the expensive land. Nearby street names like Olimpiečių and Sporto still reminds of the past when southern Žirmūnai was the heart of Lithuanian sport.

On the opposite side of Rinktinės street, a Museum of Technology operates in what was Vilnius's first power plant (1904), still crowned by a statue of personified Energy. The showcases range from old turbines, cars and Lithuanian industrial history to generic optical illusions.

The North Town (Šiaurės Miestelis) area spent the 19th century as an Imperial Russian military base, which housed a Soviet garrison after World War 2. Around the year 2000, it was heavily redeveloped and now there is a modern district of new apartments, offices, and retail. A quarter of it forms the Ogmios Retail City which is the largest shopping park in Vilnius.

A few Russian imperial barracks remain in the North Town, purposefully restored instead of facing destruction. They add some atmosphere to the district but are not a reason enough to visit on their own.

The rest of Žirmūnai is effectively a Soviet apartment borough built around the 1960s when it became the first such district of Vilnius.

Soviet Micro-Districts in Vilnius

By the 1960s Soviet urban philosophy moved from the expansion of natural city centers to the construction of new "micro-districts". Each micro-district would have a shop, a kindergarten, and many apartment blocks. Each apartment block would be built according to a similar design as the rest of them. Every micro-district would be separated from most other micro-districts by grasslands or small forests. The areas between apartment blocks would also be open spaces that are now filled by cars.

A typical Soviet district of Vilnius. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

There is little to see in most micro-districts but strolling around one of them might be interesting to fully understand where the majority (some 55%) of Vilnius inhabitants live. All the Soviet micro-districts are concentrated west of Vilnius 19th century districts. Four to eight lane trunk streets such as Laisvės Avenue, T. Narbuto street, Ozo street or Ukmergės street connect micro-districts to each other and to the city center. These thoroughfares are now commercial hubs.

• The first new Soviet borough in Vilnius is Lazdynai, constructed in 1967 – 1973.

• Karoliniškės is the second one, built in the 1970s. It was the site of the January 13th, 1991 attacks by the Soviet troops against armless people defending the Vilnius TV Tower. This tower, still the tallest structure in Lithuania and once among the 10 tallest in the world, has a public observatory. Paukščių Takas expensive restaurant that is open there rotates around in 24 hours. Streets in Karoliniškės are named after people killed in that bloody night of 1991. While Soviet troops managed to capture the TV tower their advances were halted elsewhere and after several months of propaganda broadcastings, the Soviets abandoned the tower after trashing transmission systems.

Karoliniškės also is the home for the Blessed Jurgis Matulaitis church. The construction started in 1991 but was never finished and while the building is consecrated it looks incomplete without the tower. It is a good example of the early 1990s „church building boom“ when religious freedom finally came to Lithuania.

Laisvės (Independence) Avenue with TV Tower annually converted into the 'World's largest Christmas tree'. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

• Viršuliškės was built in the 1970s.

• Baltupiai was built in the 1970s. Unlike the rest of micro-districts, it has several old buildings. The Calvary church (1700), once proudly standing in the countryside, is a popular religious pilgrimage site with its long Via Dolorosa path in surrounding park recreating the final path taken by Jesus Christ (the 7 km length and relative directions are authentic). Destroyed by the Soviets in 1962 these 35 chapels are now rebuilt. This church is so important that the local village has been renamed Jeruzalė (Jerusalem) in the 18th century; the name is still used for the modern district. This district houses Museum of Customs.

• Santariškės is the location of main hospitals and clinics of Lithuania.

• Šeškinė was built approximately on 1980. It is now famous for Akropolis shopping mall, largest in the Baltic States (over 100 000 sq. m). Vilnius's 2nd largest shopping mall Ozas is also in the same Ozo street, forming the center of a wide-scale modern development which also includes a water theme park and an 11000-seat arena. As the heart of sports (and music) in Vilnius, the area has a basketball monument and an alley where every lamppost bears an image of Lithuania's major sportsperson.

Basketball monument in front of Vilnius arena in Šeškinė. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

• Justiniškės was built in the 1980s.

• Fabijoniškės was built in the 1980s.

• Pašilaičiai was built in the late 1980s.

• Pilaitė is the last micro-district (the late 1980s – early 1990s) that was never completed (due to the collapse of the Soviet Union). It was envisioned to be so large that one-fourth of Vilnius population would have lived there, commuting to the city center by light rail. The wide central zone between traffic lanes of Pilaitės Avenue was meant for the rail line. Together with on-ramps descending nowhere, it reminds of the aborted massive visions. Nevertheless, Pilaitė is still continuously expanded, albeit following a more compact design and slower pace.

Some of the older neighborhoods such as Žirmūnai, Antakalnis or Naujininkai were also partly supplanted or expanded by Soviet micro-districts.

After Lithuania regained independence in the year 1990, Vilnius population ceased to expand. However, a few new districts were developed as people were eager to buy their own modern homes (during the Soviet occupation, the square meters of living space per one person in Vilnius used to be much lower than that in Western Europe). These new districts of high-rise apartment blocks were largely laid beyond the furthest Soviet boroughs: Fabijoniškės, Pašilaičiai, Pilaitė, Lazdynai. One exception is Šiaurės miestelis, a residential and commercial zone in Žirmūnai that supplanted a former Russian military base.

Map for Soviet micro-districts of Vilnius is joined to the Vilnius suburbs map

Suburbs of Vilnus

The environs of Vilnius are as diverse as is the city itself. Depending on which side you will leave Vilnius you may encounter luxurious manors built by once-powerful families, Muslim, and Polish villages, unique art projects, dull Soviet "proletarian" homes, and factories, "private castles" of the 1990s nouveau-riche, modern credit-funded suburbia, genocide memorials, protected nature and wooden huts where the time (seemingly) stands still.

Take note that in Lithuania (unlike many other countries) it is a common practice to expand the city limits once new suburbs are established or historical towns effectively become suburbs. Therefore most of the suburbs are legally part of the Vilnius city. Also, note that the 1960s-1980s Soviet micro districts are sometimes incorrectly referred as suburbs, but on this website they are described separately.

Northern suburbs (west of Neris river)

At the transition of Santariškės borough and forest stands the Neoclassical 18th century Verkiai manor, the most beautiful suburban manor of Vilnius. It includes 15 buildings and 36 ha park with viewpoints to the Neris valley and Valakupiai. The main palace was demolished in 1842 but two palatial servant residences remain and are popular for weddings. The Neris valley road that connects Verkiai to Žirmūnai passes the Trinapolis monastery.

Further north, the dull suburbs of Balsiai are notable for Europos parkas, a 55 ha open-air museum of local and international modern art (mainly sculptures). Most major works are at the paved path or central lawn.

Chair/Pool by Dennis Oppenheim at Europos parkas. Image ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The museum is named after Europe because the geographic center of the continent (according to one of several calculation methods) is not far away (marked by obelisk some 10 km outside the park limits).

Nearby Žalieji ("Green") lakes (Balsys and Gulbinas) help the inhabitants of Vilnius to survive the summer heat.

Northeastern suburbs (east of Neris river)

Among the more interesting suburbs of Vilnius is the forest-clad Valakupiai north of Antakalnis. Here you can see both old wooden villas and new private homes of the rich. There are two beaches where you can swim in Neris river in Valakupiai. Turniškės gated community where the leaders of Lithuania live (president, prime minister and others) is also located in Valakupiai woods. Turniškės was built in 1939 for the construction of a hydroelectric dam that was never completed due to World War 2.

Going eastwards from northern Antkalnis by Plytinės street you will encounter Kairėnai manor where the botanic park of Vilnius University is now established.

A view towards the Neris valley from Verkiai Manor viewpoint. Trinapolis monastery is visible to the right, Valakupiai beach is at the bottom. This area forms the Verkiai Regional Park, one of two protected natural zones within Vilnius city limits. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Like some other suburbs, Kairėnai is stuffed with large private homes of the 1990s dawn of the capitalism era. Many of them are built without competent architects and were planned to house entire generations of families.

Eastern suburbs

Pavilnis and Naujoji Vilnia to the east of city center have been separate towns included into Vilnius city limits after World War 2. The total population of these suburbs is 33 000, the plurality of inhabitants is ethnically Polish.

Naujoji Vilnia is the largest of the Vilnius suburbs and having been a pre-war town (population of some 8 000 in 1939) it has some historical homes, including two Roman Catholic churches, among which historicist Saint Casimir (1911) is the more impressive. A wooden Russian Orthodox church (1908) also exists. The railroad station at the borough center is holding dark memories as the Soviet regime deported some 300 000 Lithuanian people (more than 10% of total population) to Siberia through here, including small children. Many died en-route or after reaching their cold destinations. A collapsed cross, a steam engine, and two cattle cars (similar to those used for deportations) remind of the events.

An old train perpetually bound eastwards serves as a reminder of the Soviet genocide. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Aukštasis Pavilnis was built in the 1930s for railroad workers, connected to a railroad station in Žemasis Pavilnis by a winding road still having its original cobbled surface.

Pavilnis and Naujoji Vilnia are separated from Vilnius-proper by pristine Pavilniai Regional Park. Protected nature here includes the 65 m height Pūčkoriai rock exposure at the Vilnia river valley. 20 thousand years old formations are visible from the lower side after 1 km easy hike from a restaurant located in a former mill.

Pūčkoriai rock exposure (left) and the renovated Belmontas mill (right). The dam that used to power the mill is still available forming so-called Belmontas falls. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

On the upper terrace of the exposure, you may find some abandoned Polish military installations of the 1930s that failed to defend that country in World War 2. Larger military warehouses exist at Šilo street to the north, now inhabited by bats.

Southern suburbs

When arriving at Vilnius by air, Kirtimai industrial district is the first sights on the ground. Airport itself is the most shining building among countless factories.

Westwards of Kirtimai stands another industrial district of Paneriai. Cut in half by the railroad this district has a grim past as in a certain place beside the railroad Nazi Germany murdered Jews, Poles, and some Lithuanians. A museum and an unofficial memorial now stand there (the number of victims listed on it is disputed by historians as too large, however).

Keturiasdešimt Totorių (southwest) and Nemėžis (south) suburbs are known for their small wooden mosques and Muslim cemeteries that belong to the local Tatar community.

Nemėžis mosque (1909). Open in some Fridays; rooftop minaret not used for prayer calls. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Bleak Salininkai (south of Kirtimai) is a good example of a Soviet suburb with little of interest except for an atmosphere of 1980s Lithuania.

Western suburbs

Two large suburbs in the west are Lentvaris and Grigiškės. Grigiškės (on Vilnius-Kaunas highway) is a 20th-century town built for workers of a nearby paper factory, while Lentvaris is an older locality known for its Tudor style Tiškevičius family manor. Its palace has an imposing tower but is sadly partly abandoned and overgrown. Acquired by a real estate businessman Laimutis Pinkevičius in 2008 who hoped to restore the complex it shared the fate of Pinkevičius's business empire that went bust with the global economic downturn.

Trakų Vokė has another manor with a nice historicist palace although its massive garden has been partly built-up under the Soviet occupation.

Between Vilnius and Grigiškės there is Gariūnai marketplace. In the early 1990s, this outdoor frontier-like bazaar was where tens of thousands of Lithuanians tried out their entrepreneurship. The place used to attract both merchants and buyers from many foreign lands as it was the prime trading spot in the entire region. With some 10 000 traders offering their goods every morning the marketplace never lost popularity but now tries to reinvent itself as a tamed "business park". Trade area is 122 000 m2 (ranging from the original marketplace to a modern small-business mall) and 210 000 m2 used car market.

Map of Vilnius suburbs and Soviet districts. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Vilnius Churches Outside Old Town

The following are several of the most iconic Christian churches outside the Vilnius Old Town.

*Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul (Antakalnis borough, 1675) has the prettiest interior in Vilnius. It includes over 2000 white statues and bas-reliefs made to reflect the idea that life is a theater. Many Biblical scenes are depicted here in this uniform way.

*Church of the Finding of the Holy Cross(Verkiai borough, 1772, Baroque) was once built outside the city limits. It is famous for its Via Dolorosa, an 18th-century system of forest paths with chapels reminding of various events during the passion of the Christ. Unfortunately, Soviets destroyed 31 out of 35 stations in 1962. However, now the chapels are rebuilt and the several kilometers long route through local woods makes a good hike.

*Church of Blessed Jurgis Matulaitis (Karoliniškės borough, see “Soviet districts“) was started in 1991 and frankly never completed. It is consecrated now and the Holy Mass is celebrated, but without the envisioned tower this brutalist building looks blunt. It is a good reminder of the early independence era when the Roman Catholic church used the newly gained religious freedom to build new churches in formerly „atheist“ Soviet boroughs and towns. Construction and real estate was unbelievably cheap at the time, but not for long. Therefore many early 1990s church designs had to be simplified or canceled altogether. Other 1990s Catholic churches in Vilnius (St. John Bosco in Lazdynai and St. Joseph in Pilaitė) are smaller. Contemporary LDS (Mormon) ward in Baltupiai, New Apostle Church in Rasos, and Tikėjimo žodis in Pilaitė signifies that 1990s religious freedom also brought in new denominations.

Church of Blessed Jurgis Matulaitis in Karoliniškės. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

*The Russian Orthodox churches were built in every new borough of Vilnius in the 19th century under the rule of the Russian Empire. The Constantine and Michael Church (commonly known as Romanov church as it was constructed for the 300 years jubilee of the Romanov dynasty in 1909) is in Naujamiestis, the Znamenskaya Church (1903) in Žvėrynas and the beautiful Saint Alexander Nevsky church (1865) in Naujininkai . Šnipiškės has the Saint Michael Russian Orthodox church (1895) at the main Kalvarijų street, surrounded by single floored buildings once meant for teaching purposes. All these are built on Neobyzanthic style. There are more Orthodox churches and chapels dating to this era but the aforementioned four are the largest.

Znamenskaya Russian Orthodox church in Žvėrynas on the other side of the contemporary Žvėrynas bridge (1906). ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

For the locations of the churches see the maps of particular districts.

Going to and from Vilnius

Vilnius Airport is the largest airport in Lithuania, offering both low-cost and ordinary airlines. The majority of direct flights are to Western Europe. A few routes lead to the key ex-Soviet cities. The remaining destinations are mostly Southern European resorts (seasonal flights).

Vilnius Airport is built within the city limits, merely 4 kilometers away from the Vilnius Old Town. In fact, most Vilnius inhabitants live further from the city center than the Vilnius International Airport is located. As such, the airport is easily reachable by cheap public buses as well as a train. Unless there are traffic jams or you need to transfer at the train station, it is both cheaper and more convenient to use the buses.

The airport bus no. 88 goes to downtown and operates during the night as well. The other airport routes operate 5 AM to 10:30 PM. Buses no. 1 and 2 go to the stations of intercity buses and trains. The "fast bus" no. 3G passes the downtown to the Soviet districts of Vilnius, stopping only at some stops en-route.

Arrivals building at Vilnius airport

Vilnius train station and the intercity bus station are located next to each other in Naujamiestis borough. Buses travel from Vilnius to most of the cities and towns of Lithuania at least a couple times a day, with buses to the main cities leaving over 10 times a day and every 15 minutes to Kaunas.

Trains are a quicker option on a route to Kaunas. On most other routes, however, they lag behind buses, are rare and their only advantage might be a slightly lower price.

Many public bus routes of Vilnius start and/or end at the station square, therefore it is easy to reach any district from this place.

Getting around Vilnius

Vilnius has an extensive network of public buses. They reach even the most remote areas of the city as well as low-rise suburbs. The timetables to some areas may be scarce, but they are never rarer than once in two hours and usually at least one bus an hour. On the most popular routes, there is one bus every 10 or 15 minutes.

Trolleybuses generally travel on the busiest routes and their timetables are more frequent. During the morning and evening rush hours, there may be a trolleybus every couple of minutes on certain routes.

Even if you don‘t know the schedules, it is fair to expect a trolleybus to come to a stop in the next 10 minutes at the latest. This is not so with buses as many bus routes are thinly served. Therefore if you have no interest in checking schedules in advance, choose trolleybuses.

A Lithuanian-assembled Amber Vilnis trolleybus in Vilnius. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

In 2013, "fast buses" were introduced, their routes marked with the letter "G". Actually, they are the same buses as those in the other routes. The difference is that they are as frequent as trolleybuses and somewhat faster than regular public transport as they stop only at half of all stops en route. Moreover, their routes are long, making them convenient for tourists.

Note that the same numbers are reused for the bus, trolleybus, and fast bus routes (i.e. bus no. 1, trolleybus no. 1, and fast bus no. 1G are not related at all).

The best stop to catch a bus is "Stotis" near the intercity bus and train terminal, as there are routes to nearly everywhere from there. "Žaliasis tiltas" stop also has many trunk routes.

A scheme of the fast bus routes in Vilnius. Bus stop names are first and the local sight names (if available) are in the brackets. Only the stops with sights, possible transfers, or the final stops are marked. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

There is no subway or light rail in Vilnius (although there are perennial talks on the construction of rapid transit), making the public transport (even the "fast buses") rather slow compared to the other capitals.

The same one-time ticket (30 min or 1 hour with transfers possible) applies for all public transport. You can buy them at kiosks or from the driver. If you buy it from the driver it costs approximately 25% more (this money goes to the driver as compensation for the additional job).

In the case of the monthly tickets, there are both ones that apply to both types of transportation and ones that apply either to buses or trolleybuses alone. There are tickets valid for several days, useful if you will use public transport extensively.

The final regular public buses and trolleybuses depart at around 23:00, although in some stops it can be as late as 23:40. Only the airport-to-downtown bus (no. 88) operates at night.

A girl at a bus stop in Vilnius. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The timetables of Vilnius public buses, trolleybuses, and fast buses are available here. A powerful journey planning tool is also included in this multilingual website.

Car parking is free in most of Vilnius but has to be paid for in the Old Town, New Town, Žvėrynas, and southern Šnipiškės (except for the residential yards, some of which are not blocked for non-residents). The prices are lower than in most foreign and neighboring capitals.

During the morning rush hours (~7:00-8:30) avoid driving towards the downtown and during the evening rush hours (~17:00-18:30) avoid driving from the downtown as main thoroughfares get clogged.

Traveling by a taxi is not recommended as taxi drivers are known to cheat people, especially (but not only) foreigners. They inflate prices as much as 10 times. Uber is available, while Bolt is an Estonian-created ridesharing system that is even more popular in Lithuania. There are also self-drive car-sharing apps like "City Bee", although due to additional hassles to join and not that much lower price a short-term visitor is probably better with "Uber", "Bolt", or car rental.

Vilnius downtown has an automated bicycle rent system where short rent is free (if you join the system). Look for orange bicycle racks. Additionally, since the late 2010s, electric scooters became popular and they have their sharing service as well. The price is, however, not that small compared to the distance traveled.

The orange rental bicycles in Vilnius Old Town. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Shopping in Vilnius

The Vilnius's oldest and largest shopping mall is Akropolis (Šeškinė borough, over 100 000 sq. m), well known not only to the people all over Lithuania but also in Belarus. In weekends and Christmas period Akropolis may get heavily overcrowded which leads to a lack of parking.

Other large shopping malls are not far away. Ozas mall, with its extensive food court, suffers from having opened during the financial crisis of 2009 but is more spacious and convenient. Panorama mall near Žvėrynas is lagging behind Akropolis and Ozas, while the mid-sized Europa mall in Šnipiškės caters to the upscale market.

Ozas mall (Vilnius), a new competitor to the successful Akropolis chain. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

High streets of Vilnius emptied out to some extent with the advent of the shopping malls. However, there are still many upmarket shops in Gedimino Avenue (New Town), especially in its GO 9 shopping mall. Unfortunately, parking is expensive there (by Lithuanian standards).

If you want to shop the "old style" there are several bazaar-like open markets. In the suburban Gariūnai next to Vilnius many of today's businessmen started their business in the early 1990s. Just don't forget to negotiate. Kalvarijų market is a smaller marketplace close to the city center (in Šnipiškės), while the Halės marketplace is an even smaller historic one in the center itself. Today there are also a few modern markets mostly aimed at ecological food.

For groceries, supermarkets are the best option. They are located in every district of Vilnius.

The main supermarkets have working hours from ~08:00 until 22:00 or 23:00 and are open 7 days a week. Other shops may close down earlier. Marketplaces are only open in the first half of the day.

For souvenir shopping, there is the ordinary selection of t-shirts, cups, and magnets at the places most popular among tourists: Pilies street and Aušros Vartų street in the Old Town. A viable alternative is to buy your souvenirs at a supermarket - the larger ones among them have a dedicated shelf.

If you prefer regional souvenirs, there is amber (likely to be imported from Kaliningrad but turned into jewelry by the local artisans). In Pilies street you can also buy paintings by the local artists. Don't expect Michelangelo there, but the prices will be much lower than in the West (if you negotiate well enough).

Arts and crafts are also available there but if you want some real shopping, come during one of the fairs (St. Casimir, St. Baltrameaus). Many Old Town streets become large outdoor craft markets during these days.

Paintings for sale in Pilies street. Some of them depict the medieval streets of Vilnius but other topics are popular as well. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Given the stories of miracles in Vilnius, you may want to buy yourself religious goods. Christian religious paintings, including replicas of the famous Divine Mercy painting and the Our Lady of Vilnius paiting, are sold on the southern side of the Gate of Dawn.

Entertainment in Vilnius

As the capital of Lithuania Vilnius is also its entertainment center.

Nightlife, theaters, and classical music

Most of bars and nightclubs are located in the Old Town (e.g. Vilniaus street, Totorių St.) and several streets of the New Town (Gedimino Avenue and environs).

Most theaters are located in the New Town (Gedimino Avenue, Basanavičiaus Street, and environs). The plays are in Lithuanian save for operas (presented in the original language) and the Russian drama theater production (Russian). Note that operettas, unlike operas, are presented in Lithuanian.

Operas are performed in the Opera and Ballet Theater. Nearby Congress Palace is now the home of the National Symphony Orchestra. Other classical music opportunities exist in the Old Town Filharmonija. Classical music is both cheaper and less exclusive than in the West.

There are some 7 permanent drama theaters in Vilnius in addition to the troupes that lack their own buildings. Most are state-funded, but the Domino theater (Savanorių Avenue) concentrates on light-hearted comedies. Old Town doll theater performs for kids.

Cinemas, bowling, ice skating, theme parks

Main shopping malls double as entertainment hubs. Akropolis includes the iconic ice skating rink at its center. Both Akropolis and Ozas house multiplex cinemas. Bowling alleys, pool tables, children zones are also present there. Both Akropolis and Ozas are located between Šeškinė and Žirmūnai.

Vilnius largest cinema is a non-mall Vingis with some 11 halls (New Town). Boutique cinemas Pasaka and Skalvija exist in the Old Town and New Town respectively.

Vingis cinema. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Vilnius lacks theme parks but indoor water park is available near the Ozas mall.

Sports (basketball, football) and popular music

Vilnius arena (12 000 seats) near Ozas shopping mall is where the main indoor sport and musical events take place. "Lietuvos rytas" basketball team (the top sports franchise in Vilnius) plays its major home games here. Games against weaker Lithuanian teams are played in the small arena nearby. Euroleague games and the matches against arch-rivals Žalgiris from Kaunas are the most popular.

Interestingly Žalgiris is also the name of Vilnius own football team. Famous in the 1980s it failed to qualify to the main tournaments in the recent decades. The home stadium is located in Southern Vilnius. Football season is spring to autumn.

In summer the main musical events relocate to the open air Vingis Park area where some 40 000 may be accommodated.

Active entertainment

There are some unique entertainment opportunities in Vilnius.

In Uno adventure park there is a possibility to zipline over Neris river from Antakalnis to Žirmūnai.

Unlike many capitals Vilnius does not restrict the hot air balloon flights. Every summer evening you may see many of the colorful balloons in the air and you may rent one yourself (with a professional pilot and ground support team).

Hot air balloons over Old Town in a typical summer afternoon. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

In summer Vilnius downtown may also be enjoyed from a hired ship. The hire spot is near National museum.

For more natural forms of entertainment in Vilnius see the article Green Vilnius.

Green Vilnius (Parks, Cemetaries, Beaches)

A 2009 survey recognized Vilnius as the greenest capital in Eastern Europe. Furthermore, Vilnius air is the cleanest among all European capital cities.

To achieve this Vilnius urban planners intentionally skipped many areas during the city expansion. These are named "parks" but with limited landscaping some of them are in fact urban forests. They are now popular for strolling, dogwalking, or enjoying a picnic.

The oldest of these pristine zones of Vilnius is right next to Cathedral and the Castle. Known as Sereikiškių Park and the Hill Park (Kalnų parkas) it includes multiple hills with good city views, among them the Pilies (Castle) Hill, the Hill of Three Crosses (Trijų kryžių) and the Gedimino kapo (Gediminas Grave) Hill.

Larger and equally popular is the 162 ha Vingis (Bend) park to the west of New Town, hugged from 3 sides by Neris river. A former nobility hunting ground it is now a major location for summer song festivals and also hosts a rugby stadium and a WW1 German cemetery amidst its greenery. Today Vingis park forms a part of north-to-south chain of green zones which separates pre-1940 Vilnius boroughs to the east from Soviet boroughs to the west. While Vingis park is developed, much of this "Green belt" is not and there are places where one may feel to be teleported to a countryside forest after walking merely several hundred meters from high-rise residentials.

A bit further from downtown the two regional parks within Vilnius city limits (Pavilnis and Verkiai) are much better for recreation as they host some impressive scenery (Pūčkoriai rock exposure), interwar military installations and 17th-19th century manors (see Suburbs of Vilnius).

People enjoying the views from the top of Pūčkoriai rock exposure at Pavilnis regional park. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The old cemetaries of Vilnius may compete with parks in their greenness but have a different aura. To contemplate you may visit the early 19th century hilly Rasos cemetery (Southern Vilnius) or the smaller Bernardinai cemetery in Užupis (Old Town). Both include elaborate tombstones and famous burials. Antakalnis cemetery (Antakalnis borough) is the burial place for 20th century celebrities, heroes and villains. If you prefer religious minorities there is an Old Believer cemetery in Southern Vilnius, Muslim cemeteries near mosques in southern Suburbs and a Jewish zone in Sudervė cemetery (Viršuliškės borough). Sadly many famous minority graveyards were razed by the Soviets, among them two Protestant and the main Jewish one. Under the Soviet rule the tradition to bury the dead along religious lines also faded and the modern graveyards accommodate people of all communities.

While swimming is not allowed in the city center, you may swim in Neris within city limits at the beaches of Valakupiai suburb north of Antakalnis. Other beaches are available at Balsiai suburb lakes. All of these are possible to access by Vilnius public buses.

Neris river beach at Valakupiai suburb. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Day Trips from Vilnius

As the major transport hub of Lithuania Vilnius offers multiple day trip possibilities using public transport or car. The most interesting ones are:

1.The historical Trakai town with its medieval island castle, many lakes, and ethnic Karaim minority. It is the most popular day trip from Vilnius. It is easy to reach by bus and by train (28 km to the west).

2.Rumšiškės open-air ethnographic museum is a collection of 19th-century buildings relocated from all over Lithuanian countryside. 78 km westwards it is well connected by a four-lane Vilnius-Kaunas highway that is traversed by frequent buses.

3.The Polish-speaking Medininkai borderland area is famous for a Romanesque 14th-century castle with a small-but-modern tower museum, the Soviet-led Medininkai massacre of 1991 and Aukštojas hill, its 293,84 m making it the highest location in otherwise flat Lithuania. 30 km east of Vilnius. A far call from Trakai island setting the out-of-the-beaten-path Medininkai castle is preferable for those who hate flocks of tourists.

4.Kernavė Castle Hills are the location of Lithuania's 14th-century capital but its multiple wooden castles and town have since turned to dust, making the location more interesting for nature lovers than cultural buffs. A local museum has a nice archeological collection, however.

History of Vilnius

The tolerant capital of the largest medieval state (Until 1655)

According to a legend, Vilnius was established by duke Gediminas in the early 14th century, after his dream of an iron wolf was so interpreted by a pagan oracle Lizdeika. Modern historians, however, usually claim that the city is at least as old as the Lithuanian state itself and that the country‘s first Christian church built by King Mindaugas in the 13th century stood at the exact same spot where the Vilnius Cathedral stands today.

Whatever its beginnings were, Vilnius became an important city by the 14th century. It had received Magdeburg city law in 1387. After the conquests of Grand Duke Vytautas, Vilnius came to be the capital of what was at the time the Europe‘s largest country, stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. It was a very tolerant city where Muslim Tatars from Crimea, Lutheran German merchants, Jewish craftsmen, the Catholic Lithuanian and Polish elite, pagan-leaning Lithuanian commoners, and Orthodox Ruthenians lived side-by-side peacefully, each group building their own temples in their own streets and districts.

In this era, the irregular-layout Old Town developed, walled in 1503. As the richness of the city grew, more and more palaces, churches, and monasteries adorned its narrow streets. Not even the 1569 Union of Lublin (which created a Polish-Lithuanian confederacy with capital in Warsaw rather than Vilnius) was able to defuse the importance of the city as the Kings still used their palace here. Vilnius University was established in 1579 by the Jesuits, becoming a primary center of science and education in the Eastern Europe.

Subačiaus gate of the Vilnius city wall (painted by P. Smuglevičius in 1785). This gate together with the wall was demolished by the Russians in early 19th century. Only some fragments and the Gate of Dawn remain today.

Where to see the era today? The Gothic churches of Saint Anne, Saint Francis, Saint Nicholas, and some others in Maironio, Šv. Mikalojaus, Trakų streets (all in the Old Town) date to this era (even if their interiors have been modified). The old campus of Vilnius University also survived the historical ravages almost intact. There are some very old buildings in Pilies street.

The era of lavish churches and impending doom (1655-1795)

The prosperous centuries came to a horrible halt on 1655 when the strengthening Russia (Muscovy) invaded and sacked the city in a long campaign of looting, mass-murdering and raping. The days of Poland-Lithuania as a great power ended, and so were the days of Vilnius as a seat of power. Vilnius palace became neglected and the Polish-Lithuanian Kings ceased visiting it. Furthermore, the Russian (Orthodox) and Swedish (Lutheran) invasions eroded the remarkable religious tolerance.

Although no longer one of the Europe‘s main cities, Vilnius continued to exist. The uncertain future at mercy of the surrounding great powers encouraged the local noble families to secure their afterlife by building lavish Baroque churches that still crown the city skyline today. By that time, Polish-speaking Catholic culture had become the elite one as many local Lithuanians had abandoned their language in favor of the more prestigious Polish.

The knot around Poland-Lithuania was tightening and the country started to lose lands rapidly in the late 18th century. In 1795, Vilnius was captured by the Russians who were to stay for 120 years.

This painting by J. Peška immortalizes the heart of Vilnius in 1808 when it still looked much as it did in late Poland-Lithuania era. The remains of the castle were still quite extensive, while large churches, such as the Cathedral (pictured), dominated over small residential buildings even more than they do today. In the foreground, you can see the place where Gedimino Avenue is today. In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth era, this was a poor neighborhood of tanners.

Where to see the era today? The Baroque churches in Vilnius Old Town and former suburbs (Antakalnis, Verkiai) are your best option, as well as many manors and other stately buildings in the Old Town.

Industrial era under the Imperial Russian rule (1795-1918)

After Vilnius was annexed to Russia in 1795, it continued to be a backwater with a population of 50 000. However, Vilnius University remained a major intellectual center with various secret societies swiftly established, such as filaretai or filomatai, each of them aimed at critically studying history and potentially restoring the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Knowing this, the Russians closed the Vilnius Univesity in 1832 (after a failed Polish-Lithuanian revolt) forcing the Lithuanian elite to seek education in Saint Petersburg. However, Vilnius remained an administrative seat (the capital of Russia's Northwestern Krai, roughly comprising of today‘s Lithuania and Belarus). As such, the government wanted to make the city look more Russian. Some of the Catholic church buildings were converted to Russian Orthodox or secular use, some others demolished, monuments for czars and governors were constructed.

The reconstruction of Saint Nicholas Orthodox church changed western-style architectural details into eastern style Neo-byzantine ones, 1863-1864, lithographies by I. Trutnev.

A true possibility to change the face of Vilnius came in 1860 when the industrial revolution finally reached Lithuania. That year the first train of the new Saint Petersburg-Warsaw railroad arrived at Vilnius. Other amenities of the era came to the city as well, even if lagging several decades behind the Western Europe: gas lighting became available in 1864, horse-drawn tram in 1893, electricity in 1903, and public buses in 1905.

Technological changes implicated social changes and a process of rapid urbanization began. A grand new civic center was constructed to the west of the Old Town (it is known as New Town), to be joined by largely wooden suburbs of Žvėrynas, Šnipiškės, Naujininkai, Rasos, Žvejai and Naujieji Pastatai in the 1890s and 1900s. The main extensions were planned to follow a grid layout that was anchored on large new Russian Orthodox churches. The new wide streets were named after locations and heroes of the large Russian Empire. With the Lithuanian language banned in 1863, the official public inscriptions were also in Russian.

The final decades before the World War 1 witnessed the most massive construction. Businessmen conceived 4 to 6 story buildings in the New Town, full of rental apartments, hotels, trade rooms for their businesses and smaller-yet-elaborate so-called urban villas for their own residences. Many stately administrative buildings were erected, such as the enormous Railways HQ. On the eve of the World War I, Vilnius had a population of over 210 000.

No ethnic, religious or linguistic majority existed in the Vilnius of 1890s after tens of thousands Russians and Jews moved in (Vilnius had been among the few cities where the Russian Czar would permit Jews to freely settle). But even this policy of cultural dilution failed to promote assimilation.

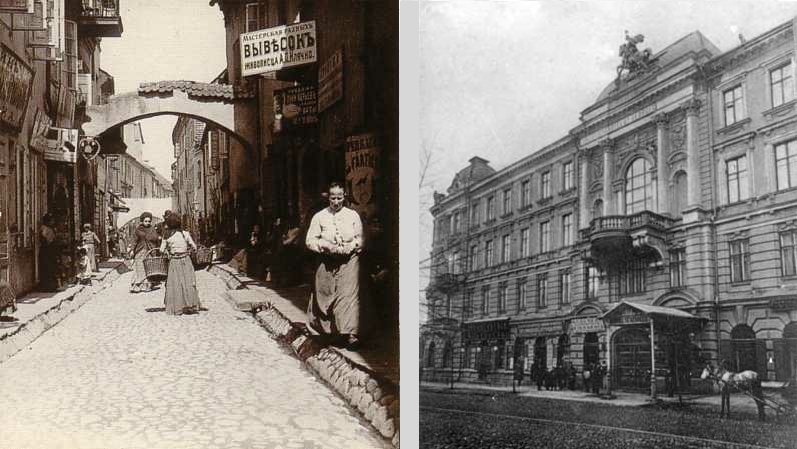

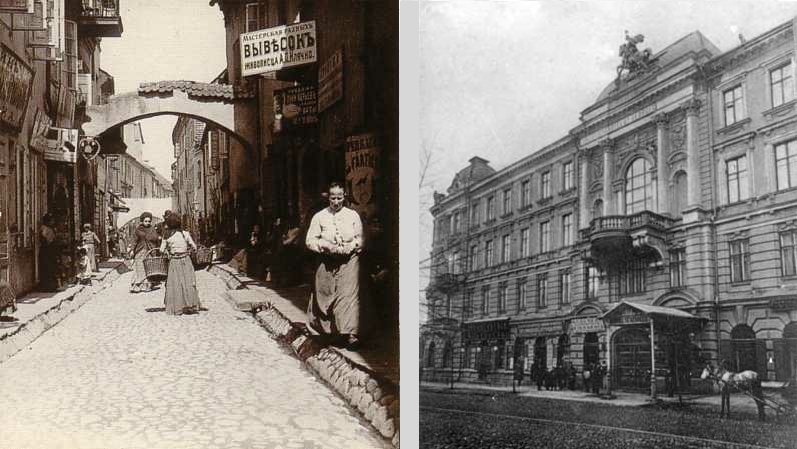

Two of the many faces of pre-war Vilnius. A street in the Jewish district, Old Town (left, 1898, S. Fleuri) and the new Saint George hotel with a horse-drawn tram in front of it in the New Town (right, 1910, A. Fialko). The pictured area of Jewish district was demolished by the Soviets in mid-20th century while the Saint Geoge hotel still exists in Gedimino Avenue, now refurbished into prestigious apartments.

The Lithuanian National Revival turned Vilnius into a capital once again, even if a shadow one. With the scrapping of some anti-Lithuanian policies in 1904, the first Lithuanian-language daily newspaper "Vilniaus žinios" became published here by the Vileišis family. In the year 1905, the Great Seimas of Vilnius convened in the city, declaring an aim for an autonomous Lithuanian country that soon turned into a drive for independence.

Where to see the era today? New Town (Naujamiestis) borough still boasts pre-war stately buildings and Orthodox churches, once visited by the career government workers from Saint Petersburg. In Žvėrynas and Šnipiškės you may catch a glimpse of how poorer suburban people lived at the time (in the case of Šnipiškės some live that way even today, lacking basic amenities). In Bernardinai and Rasos cemeteries (Old Town and Southern Vilnius boroughs respectively) the elite and the commoners of the era are interred, while Markučiai manor (Southern Vilnius) is now a museum partly dedicated to the Russian nobility of the era.

The era of Polish rule and conflict over Vilnius (1918-1939)

With the communist revolution engulfing Russia and Germans surrendering in World War 1, the rulers of Vilnius changed some 10 times in the years 1918-1922. The city was culturally important to four different ethnicities: Lithuanians, Poles, Jews, and Belarusians. Furthermore, both Russian monarchists and communists wanted to restore the former boundaries of Russia, with Vilnius inside them. Of these six entities, only the Jews lacked a military force.

German army captures Vilnius during the World War 1 (1915), walking past a Russian Orthodox church the Russians have constructed in 1913, merely 2 years ago. This was the first change of ownership of Vilnius in more than 100 years. In the next 10 years, however, Vilnius would change ownership approximately as many times as in all its previous history put together.

Having beaten back the Russians who in turn subdued the Belarusians, Poles and Lithuanians were the last two left to quarrel over Vilnius. In 1920 Polish irregular forces captured the city in breach of the previous treaty of Suwalki. This was the start of a painful final divorce of Lithuanian and Polish nations.

Lithuania never recognized the loss of Vilnius and remained at a state of war with Poland. International mediation failed. The plight for Vilnius was a major topic at any interwar celebration in Lithuania where the choirs would sing „Mes be Vilniaus nenurimsim“ („We won‘t calm down without Vilnius“) hymn. Many streets and squares in Lithuanian towns were renamed after the city, „Vilnius oaks“ were planted, „Union for the Liberation of Vilnius“ established.

Funeral ceremony of the heart of Polish president J. Pilsudski passes the Rotušės square in Wilno in 1935. Like many Polish-speaking people of Lithuanian descent of the era, J. Pilsudski called himself a Lithuanian but did not believe in independent Lithuania. He sought to establish a large country that would encompass Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, and Belarus and would use Polish as lingua franca. His dreams were behind the annexation of Vilnius region to Poland in 1922.