Religion in Lithuania: An Introduction

In the globalized world of 21st century, few would be surprised by multi-religious cities. However, in Lithuania, the multi-religious atmosphere is centuries old. The 19th century Vilnius had temples of over 10 different religions, many of them non-Christian. Lithuania is a unique crossroad of the East and the West in that here you can see the centuries-old heritage of many different faiths.

Today most (some 85,9%) Lithuanians are Roman Catholic and the interwar Lithuania was a very religious society. However the long Soviet occupation (1940-1941 and 1944-1990) with its anti-religious policy brought in a flavor of sometimes radical atheism (6,8% irreligious). It also triggered a decline in religious services attendances and a more clandestine role of religion, which is still largely invisible in public places.

The interior of a Roman Catholic Cathedral in Šiauliai city (Samogitia region). Relatively plain interiors like this are common ir newly restored churches once damaged by the Soviets and wars.

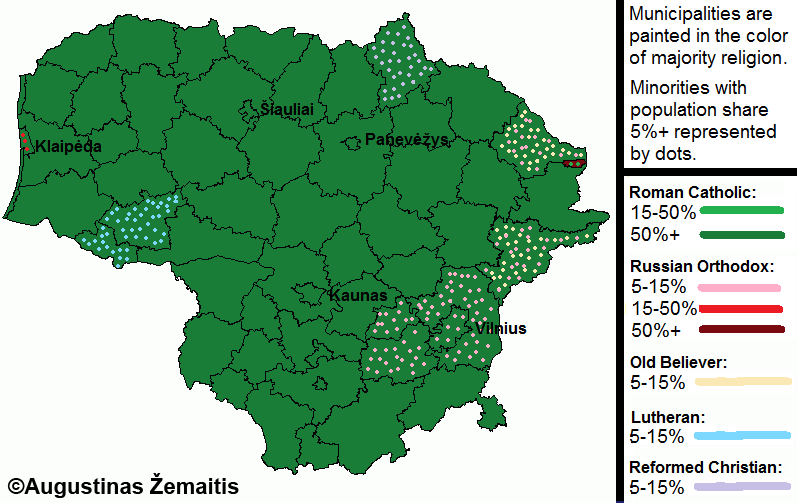

Second largest faith is the Russian Orthodoxy, followed by 4,6%, mostly ethnic Russians. 0,9% of the population are Old Believers, whose Russian ancestors received refuge in Lithuania when they were persecuted in Russia for refusing to adhere to the Nikon’s religious reform. Lutherans, 4th largest religion (0,7%), enjoy a centuries-old stronghold in Klaipėda Region, while the Lithuanian center of the Reformed Christianity (0,2%) is the Biržai district in the northeast.

Four other faiths are considered traditional by the Lithuanian law, and they are:

*Sunni Islam, adhered by Tatars whose ancestors were brought as soldiers to these areas by Vytautas the Great.

*Judaism, the religion of the Jewish community, severely weakened by the Nazi Germany's Holocaust, Soviet atheism and the emigration to Israel.

*Karaism, an old offshoot of Judaism practiced mostly in Vilnius and Trakai.

*Uniate Christianity (Eastern Catholicism), a form of Christianity whose devotees recognize the Pope as an authority but follow the Eastern orthodox liturgy.

Each of these faiths is now followed by 0,1% or less population but their centuries-old communities are important for Lithuania’s history and culture.

Since independence, the number of adherents of new or foreign religious movements increased but they all put together remain under 1%. 0,5% belong to minor Christian faiths and 0,2% are neo-pagans.

Lithuania recognizes religious freedom. Traditional religious institutions are treated like any cultural institutions. The state could support them (but such support should be proportional to the number of their followers).

Map of Lithuanian religious communities. In most municipalities, 90%+ people are Roman Catholic. Significant religious minorities are concentrated in particular areas. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Roman Catholicism in Lithuania

With some 86% of the population its followers, Roman Catholicism is the main faith of Lithuania since the 15th century. It is thus closely associated with Lithuanian culture. While Lithuania has no state religion, the laws generally permit support for religion by public institutions as long as such support is proportional to the number of adherents of those religions in the area. As Catholicism has the most followers almost all over Lithuania, this leads to it enjoying a semi-official status in some cases (for example, the public TV station provides a live coverage of Catholic masses during the key festivals).

Vilnius Cathedral is likely the oldest Roman Catholic church in Lithuania, dating to approximately 1251. The current façade was created in Neoclassical style in 1801. Like many churches, the Cathedral was nationalized by the Soviets and its sculptures of three saints torn down (they were rebuilt after independence). Most of the key public masses are held here. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Roman Catholicism in Lithuania withstood both the Reformation (16th century) and the church closures under the Russian Empire (19th century). In 1940-1990, Catholicism served among primary forces of defying Soviet occupation and publishing the anti-Soviet “Chronicles of the Catholic Church” that documented the persecution of Lithuanians. As such, the Catholic church has gained an image of the "defender of truth and human freedoms" in Lithuania, which it lacks in the West.

Many small Lithuanian towns or villages are adorned by tall elaborate churches, mostly dating to the early 20h century when the Russian Imperial ban of new Catholic churches was lifted. In other places, older wooden churches (18th – 19th centuries) remain. They are great examples of traditional people’s architecture.

Next to the roads, you may still see some large crosses and small chapels erected by the local people. Lithuanian cross-making is inscribed into UNESCO list of immaterial heritage and the best place to see it is the Hill of Crosses near Šiauliai.

Interior of a modest Žagarė church, with explanations. Every Catholic church has a Main Altar where the priest celebrates the Mass. The high point of every Mass is the distribution of Holy Communion. This wine and bread, representing Jesus's flesh and blood, is kept in the tabernacle outside of Mass. Glowing eternal lamp indicates their presence. Bible and sermon are read at the front pulpit (ornate side pulpits were used to make the priest heard better before the microphone/speakers era). Followers sit, stand or kneel (depending on the time of Mass) at the benches. Stations of the cross are 14 paintings or bas-reliefs representing the Passion of the Christ. There are many other paintings depicting saints and Bible scenes, the most important ones hanging behind altars. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

But probably nowhere Roman Catholicism is felt as much as in Vilnius Old Town, where there are many church spires of different periods gone by, from 14th to the 18th century. There are also several miraculous paintings that are visited by pilgrims from far away in Vilnius: the Divine Mercy and the Mary of the Gates of Dawn are the prime examples.

Another famous miraculous painting exists in Šiluva. While the elaborate processions to the holy sites across Lithuanian countryside are less popular today than they were 100 years ago, the religious town holidays are still the main event of the year in many places.

The annual religious festival at the Hill of Crosses. Together with the ones at Šiluva and Žemaičių Kalvarija, it is among the Lithuania's largest, often televised by the national TV. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

As the Lithuania’s major religion, Roman Catholicism was the prime target of the Soviet anti-religious drive. The Soviets closed many churches and all the monasteries. After independence, most of these buildings have been reopened and repaired but a lack of money means that many others still stand derelict with their priceless artworks destroyed. Although the religious practices were reborn, they are still nowhere as prevalent as they were before the occupation. Only a few percent of Lithuania's Catholics actually go to mass every Sunday (nominally a requirement for the believers).

Catholic priests and other officials beging a construction of a new church. After independence, there was a boom of constructing new churches as many Soviet-built borougs and towns were churchless. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Currently, Lithuania is the world's northernmost and Europe's easternmost Catholic-majority country.

See also: Christian holidays in Lithuania, Top 10 Christian locations and activities in Lithuania

Orthodoxy in Lithuania

Orthodoxy is the second-largest faith of Lithuania, however, it is the followed nearly entirely by ethnic minorities, primarily Russians. This is in stark contrast to Latvia, Estonia, or Finland where there are many Orthodox people of titular ethnicity. Interestingly, a separate Lithuanian Orthodox Church doesn’t even exist. All the Orthodox Church buildings are directly subordinated to the Russian Orthodox Church based in Moscow.

Vilnius, for centuries the capital of multi-religious Grand Duchy of Lithuania, had Orthodox churches since the 14th century. But this faith came to the other parts of Lithuania only after the annexation by the Russian Empire in 1795. Czarist policy of Russification brought large domed churches to the new wide squares and straight avenues, and so even today in Vilnius 19th century districts the Orthodox churches outnumber the Roman Catholic ones. Every major town of the 19th century Lithuania received its own Orthodox church (more than a single one in Vilnius and Kaunas). A minority of these buildings were ceded to the Roman Catholic community after the 1918 independence, but the iconic neo-Byzantine facades and domes remained intact even there.

Saint Nicholas church in central Vilnius is among the few Orthodox churches built before the Russian Imperial occupation of Lithuania in 1795. It was established as early as 1350, the current building dates to 1514 with major upgrades in 1865. It served the Uniate community in the 17th and 18th centuries.

In an Orthodox church, you may feel as being suddenly transferred to a land further east because there are usually no Lithuanian words whatsoever. Even signs for tourists are typically available only in Russian and English. The website of the Orthodox Church in Lithuania lacks any non-Russian version.

The bond between the Russian nation and the Orthodox church continued well into the 20th century. Even the anti-religious Soviets had preferential treatment of the Orthodox church in Lithuania. Under the Soviet rule, a large number of Catholic churches were closed down, whereas almost every Orthodox church remained open. Thus there was an equal number of open Catholic and Orthodox churches in Soviet Vilnius even though Catholic devotees outnumbered Orthodox ones by 10 to 1. The only monastery permitted to operate in Lithuania after the Soviets disbanded all the others was the Russian Orthodox Holy Spirit Monastery in Vilnius.

There are 43 Orthodox churches in Lithuania with the most interesting being in Vilnius. 4,6% follow this faith.

The interior of the Russian Orthodox church. There are no pews as people stand during the masses, which take some 2 hours. That is double the duration of a Catholic or Lutheran mass, as some of the parts of a Russian Orthodox Mass are repeated several times. At the front of the church is the iconostasis:

a 'wall' full of religious paintings. A priest performs some rituals behind it, invisible to the church-goers. However, the iconostasis opens at the pinnacle of the Mass.

Old Believers in Lithuania

Perhaps the most secretive traditional religious community in Lithuania, the Old Believers came as refugees from Russia in late 17th century. They settled in small villages away from the main roads. Some of these are so well hidden that even today they can only be reached by minor dirt roads, and only with a good paper atlas instead of a GPS system.

Many such villages have since died out and their houses are crumbling but perhaps more frequently than not the church of such village is still offering rare celebrations of the Holy Mass for the Old Believers who are periodically returning there from larger cities (outside these rare dates the churches are locked). Today the cemetery is often the liveliest place in such localities as the relatives come to visit the graves of their forefathers.

Some of the Old Believer village churches are true masterpieces of wooden architecture, such as the one in forest-clad Perelozai (Jonava District Municipality) or the one in Jurgėliškė (Švenčionys District Municipality) with its tower unfortunately collapsed.

Two Old Believer village churches in Aukštaitija region with two different fates. The elaborate tower in Jurgėliškė, Švenčionys district (left picture, 1935) leaned more and more every year until it finally collapsed in 2008 (the picture was made after the collapse). The church in Perelozai, Jonava district (right picture, 1905) stood decrepit for decades but was refurbished recently. All this despite Perelozai being completely abandoned in the 1970s and all the wooden homes crumbled since. Both churches are still used for rare masses. Both of them may only be accessed by gravel or dirt roads. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The Old Believer community (and its church with a shiny dome) in Vilnius is also away both from the city center and main thoroughfares, in the southern district of Naujininkai. This community, however, is livelier, and the 3-hour long masses led by ordinary people rather than priests are still frequent there.

Old Believers think that after the Nikon reforms of the Russian Orthodoxy (17th century) no priest ordination is valid. So they have no hierarchy and even no altars, the iconostasis making the back wall in their churches. Traditional Old Believers even used to refuse to eat from the same dishes as people from other faiths and so they had separate plates and cups for non-Old Believer guests.

There are 43 Old Believer churches in Lithuania. Most of them are located in the Aukštaitija region and some in Dzūkija. 0,9% of the total population follow the faith.

An urban Old Believer church in Kaunas, established in 1906 by those Old Believers who moved away from the villages. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Lutherans in Lithuania

It may surprise you, but the Roman Catholic Lithuania you see today is only one part of the historical Lithuanian nation. The other one, known as Lithuania Minor, had never enjoyed independence. Until the 20th century it was a part of Prussia and so the local Lithuanians became Lutherans.

At one time the Lithuanians (known there as “Lietuvininkai”) were the majority in a quarter of East Prussia province, but rapid Germanization of the 19th century diluted their stand. The final blow to “another Lithuania” was the Soviet genocide of the 1940s, when most lietuvininkai were either murdered, deported, or chosen the path of refugees together with local German civilians (also Lutheran) who were expelled by the advancing Red Army.

A small red-brick Lutheran church in Juodkrantė village, Neringa (Curonian spit), built in 1885. These days Catholic masses are celebrated here as well. Lutheran mass is still sometimes celebrated in German. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

East Prussia was annexed by the Soviets and Poland, then repopulated. What is now Kaliningrad Oblast was swiftly repopulated with Russians, whereas the northernmost part of former Lithuania Minor, so-called Klaipėda Region, was largely repopulated by Lithuanians from Lithuania Major.

Even so, the Klaipėda Region still has red German-style Lutheran churches in many larger towns and while their congregations are long since surpassed by Catholics and Atheists, some 5% of people in these rural areas are lietuvininkai descendants still adhering to the Lutheran faith (down from 91,7% in 1925). Lutheran communities also exist in the major cities, in southern Samogitia (Tauragė area), in some localities near the Latvian border and in western Sudovia.

Unfortunately, the most beautiful Lutheran churches in Klaipėda and their massive spires were torn down by the Soviets after the World War 2. What remains are largely town and village churches built of the iconic German red bricks. They too were looted during World War 2 and closed throughout the Soviet occupation but most buildings survive.

A Lutheran church in Tauragė boasting statues of Martin Luther and Martynas Mažvydas at its entrance. Mažvydas was a 16th century author of the first Lithuaian-language book. At the time, Catholics did not encourage popular literacy, leading to Lithuanian Lutherans becoming instrumental in creating and advancing the Lithuanian literature. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

In 1925 the Republic of Lithuania had over 200 000 Lutherans (9% of the population, the largest religious minority at the time). The census of 2001 found 19 637 Lutherans (0,6% of the population). Such a decrease means that while the old network of parishes was partly reestablished after independence, the mass is typically celebrated less than weekly in the reopened village churches.

The Lutheran cemeteries were also looted and demolished by the Soviets. The cemetery in Šilutė left between existence and destruction serves as an unofficial memorial for the losses suffered by the community.

Reformed Christianity (Calvinism) in Lithuania

This branch of Christianity follows the Jean Calvin teachings. It came to Lithuania in the 16th century and was favored by certain nobles of Radvila family. They were based in Kėdainiai and to this day the small town still is dominated by a Reformed church structure somewhat reminiscent to Ancient Greek temple (rather than by a Roman Catholic spire).

The area where Reformed Church gained a real foothold, however, was in the northeastern Lithuania in the town of Biržai and the surrounding countryside (also a Radvila domain at the time). There are many reformed churches in the towns and villages of the area and some 10% of the population still profess this faith.

The smaller Christian denominations in Lithuania were hardest hit by the Soviet occupation because their small communities meant an inability to withstand Soviet persecutions. As such, some Reformed Christians converted to Roman Catholicism in 1940 – 1990, decreasing their overall share from 0,5% to 0,2%.

Reformed Christian communities and churches also exist in some of the main cities.

Interior of the Biržai Reformed Christian church (1874). Plain for its era the interior reflects the Reformed Christian beliefs. On the wall in front of the congregation (where sacred paintings, crucifixes and stained glass windows dominate in the other denominations) a sole inscription VIENAM DIEVUI GARBĖ (GLORY TO ONE GOD ALONE) proudly hangs. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Sunni Islam in Lithuania

Islam came to Lithuania well before many other European nations when Grand Duke Vytautas the Great brought Muslim Tatars from the southernmost limits of his lands to defend Vilnius and the boundaries. This happened in the 15th century.

The passing centuries blended the medieval soldiers into the Lithuanian landscape. Their square wooden mosques (19th century) are more reminiscent of Lithuanian village houses than Arabic religious buildings. These mosques are unique and with only three left (in Raižiai, Nemėžis and Keturiasdešimt Totorių, the latter two near Vilnius) – a sight not to miss for anybody interested in Islam.

A mosque inspired by Arabic style was built in Kaunas for Vytautas the Great jubilee in 1930.

The 20th century brought new Muslims to Lithuania, firstly from the Soviet Union and after independence – from the volatile Middle Eastern and African lands. These new Muslims may be already outnumbering the traditional Tatar community. But, as of now, there is not even a mosque in Vilnius since the Soviets torn down the old wooden Tatar one that until 1968 stood in the old district of Lukiškės.

The practice of faith itself was heavily impeded under the Soviet occupation with most mosques closed, Quran hardly possible to get and Hajj outlawed. When the independence (1990) brought back the religious freedom Islam made some comeback in its communities.

There were almost 3000 Muslims in Lithuania during the 2001 census (some 0,1% of the population). Most Lithuanian Muslims follow Hanafi madhhab.

A traditional wooden mosque in Raižiai village (Alytus district municipality, Dzūkija), famous for its minbar made in 1686. The current mosque itself was built in 1889. Minaret is above roof but is not used for the original purpose. The door to the left is used by the women whereas the door to the right is the entrance for men. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Judaism in Lithuania

Lithuania is so important in the Jewish history that Vilnius is sometimes called the “Jerusalem of the North”. It is here that the famous Talmud commentator Elijah (Gaon of Vilnius) lived in the 18th century. Jews once made the majority of inhabitants in a few Lithuanian towns and a significant minority in many others. The type of Judaism followed in the Lithuania's prime yeshivas influenced Judaism worldwide.

Jewish religious communities have been massively drained by emigration since mid-19th century, but the Nazi German Holocaust (1941-1944) and the Soviet atheist policies (1945-1990) proved to deal the final blow to most of them, leading to an abandonment of the yeshivas and many synagogues. Soviets then destroyed many religious structures, among them Jewish cemeteries (reusing some gravestones for entertainment buildings) and the Vilnius Great Synagogue. These Soviet policies were not unique to Judaism as other religious groups shared a similar fate (atheist Jews, on the other hand, were influential in the Soviet Union, this hastening the decline in Judaism followers).

An abandoned synagogue in Alytus (Dzūkija region). ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

What has survived is still impressive albeit only two synagogues are working now (in Vilnius and Kaunas). In some cities and towns, such as Alytus, Kėdainai, Pakruojis, Švėkšna or Joniškis, there are former synagogues still standing, some of them converted to another use, but many others abandoned and derelict. Approximately 80 synagogues survive, 13 of them wooden. They are usually harder to spot than the local churches because of the lack of tower and a less visible location.

A legacy of the Soviet occupation is that only 30% percent of Lithuania’s ethnic Jews are of the Jewish faith (nearly half of them aged 60+), with most younger Jews now professing no religion. This led to serious disagreements between religious and secular Jewish communities over who is the real descendant of the interwar Jewry and who should receive back the buildings that were nationalized by the Soviets and compensations. The new religious possibilities after years of a spiritual vacuum also caused disagreements inside Vilnius Jewish community over what type of Judaism should be followed in Vilnius Synagogue (Hassidic Chabad Lubavitch that made inroads to Lithuania in the 1990s or the traditional Litvak).

That said, 2010s saw a limited rebirth of the Jewish faith and after a long hiatus, it became possible to see some Jews in the traditional Orthodox clothes, although very few and mainly around the Vilnius synagogue at the prayer time.

Renovated synagogues in Joniškis. Like most renovated synagogues, they are no longer used for religion, even if returned to the Jewish community. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Eastern Rite Catholicism (Uniates) in Lithuania

No other faiths had their fortunes so greatly depending on the political climate as did the Uniates, currently centered around their church of Holy Trinity in the Old Town of Vilnius.

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was ruled by the Catholic Lithuanian leaders but after its major expansion to modern-day Belarus and Ukraine (14th-15th centuries), the majority of its population were Eastern Orthodox Slavs. There were many attempts to solve these divisions. Grand Duke Vytautas devoted much time to influence the contemporary religious leaders to solve the East-West schism of Christianity altogether.

This proved to be far-fetched and so the later Grand Dukes of Lithuania opted to solve the problem locally rather than globally by establishing the Uniate church in 1596 (Union of Brest). Its adherents were allowed to continue the Eastern Orthodox religious practices but recognized Catholic institutions (including the Pope).

With the annexation of Lithuania to the Russian Empire in 1795, the state-sponsored role of the Uniate church ended almost overnight and its many churches and 95 monasteries were closed down or ceded to the Russian Orthodox church. The Uniate church was also among the most persecuted ones during the Soviet occupation. The result is that the Uniate Christianity is now very weak. Most of its 350 adherents still are, as they always used to be, Eastern Slavs, primarily Ukrainians.

A monumental gate to the Basilian monastery and the Holy Trinity church in Vilnius Old Town. The only operating Uniate church left in Lithuania it surely saw better days. Masses are celebrated in the Ukrainian language. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Karaism in Lithuania

With only 290 adherents the Karaite faith is the smallest of the traditional religions in Lithuania. Considered by many Jews to be a type of Judaism, the Lithuanian Karaism followers have always considered themselves to follow a different faith.

Unlike the Jews, the Karaites do not recognize Bible commentary (such as the Talmud) as divine. Every Karaite is expected to understand the Old Testament (especially the Ten Commandments) himself/herself. Having originated in 8th century Iraq and further developed in Eastern Europe the Lithuanian Karaism blended in many Christian and (especially) Islamic practices (for example, human and animal depictions are banned). Other traditions (such as many holidays) are unique to Karaism.

The definition of “Karaite” attracted a surprising interest from governmental institutions knowing that these communities never numbered more than several thousand in the Eastern Europe. They were regarded as a separate community by the Russian Empire where they enjoyed more privileges and less discrimination than Jews. Even Nazi Germany had a separate policy on the Karaites and this saved the community from the persecutions which the Jews had to face.

Karaite kenesa in Trakai. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Although their names are incorrectly used interchangeably, Karaism and Karaite Judaism (a form of Jewish faith) have differing religious practices.

Karaites pray at Kenessas and currently there are two Kenessas in Lithuania: one in Trakai and one in Vilnius. The Karaite community in Trakai is the liveliest one. Until the 19th century, Karaites enjoyed a separate town charter in Trakai and currently there is a Karaite museum there. The iconic three-windowed Karaite homes in Trakai high street are another part of their heritage.

Almost all Karaites are ethnic Karaims, a certain Turkic ethnicity. Both Karaim and Hebrew languages are used in their liturgy.

Karaite kenessa in Žvėrynas Borough, Vilnius. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Romuva (Neo-Paganism) in Lithuania

Romuva is a neo-pagan community that attempts to restore Lithuanian paganism. Only in 1387 was Lithuania officially Christianised, the last European state to abandon paganism. In spite of this few credible sources describe the pagan Lithuanian practices which have long since died out. Therefore many historians regard the 20th-century attempt to restore Lithuanian paganism to be a mere speculation which must be quite unlike what the real Lithuanian faith used to be. This is why unlike other old religions Romuva does not enjoy the traditional faith status in Lithuania.

For Romuva adherents, however, their religion is the one that the Lithuanians should follow. Many of them regard Christianity as having been forced upon Lithuania and also not well suited to the Lithuanian nation.

While traditionally Lithuanian nationalists used to be Roman Catholic, today many young nationalists choose to be neo-pagans instead by claiming that this religion is the one original to Lithuania.

Žemaičių alkas (literally the Samogitian pagan shrine) in the coastal resort of Šventoji is among the few pagan religious structures in Lithuania. It was built in 1998 with the aim to reconstruct a 15th-century shrine that used to stand on the Birutė hill in Palanga. Based on archaeological finds it is a group of variously shaped wooden poles, each of them representing a different deity. A sacred fire is lit between the poles during the ceremonies. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Romuvan celebrations take place outdoors near sacred fires and are led by vaidila, while krivis is the leader of the whole community. There is an extensive pantheon of gods and goddesses, most of them related to particular forces in nature, such as the thunder (Perkūnas), or to lifetime events. Like other neo-pagan faiths, Romuva has no scriptures and relies on historical tradition instead. It accentuates the link between the man and nature and sees other polytheistic traditional faiths, including Hindu, to be more acceptable than either monotheism or atheism.

Note that sometimes it may be hard for an outsider to distinguish a historical re-enactment from a real religious practice. For instance, pagan bachelorette parties are chosen not only by pagan brides.

Neo-pagans are the fastest-growing religious community in Lithuania. Its membership increased from 1270 to some 5100 between censae years 2001 and 2011. With 0,2% of the population its followers, neo-paganism is now the country's 6th largest faith.

A Romuvan mid-winter (Pusiaužiemis) celebration in Vilnius, here celebrated inside around an improvised bonfire made of candles. Krivė (female Krivis) stands in the middle. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Not every Lithuanian neo-pagan is a Romuva adherent, however. Because of the scarcity of exact knowledge of prehistoric Baltic religious practices, there are various interpretations or guesses, sometimes conflicting with each other. The questioned facts range from the existence of top gods/goddesses to the inclusion of certain esoteric or New Age practices, suggested by some non-Romuvan neo-pagan groups.

See also: Lithuanian mythology and folklore, Top 10 pagan places and activities in Lithuania

Minor Christian Faiths in Lithuania

In addition to the traditional Christian communities, there are numerous smaller ones, consisting of 0,5% of the population (12 000). Jehovah Witnesses boasts the largest congregation with ~3000 followers. Pentecostals come second with some 1850, Baptists 1350, Tikėjimo žodis 1000, Charismatic church 950, Seventh Day Adventists 900, Church of Christ 500, New Apostle Church 420, Methodists 360, LDS 130 followers. Furthermore, some 1200 are non-denominational protestants and 1300 are non-denominational Christians.

Despite some of these faiths reaching Lithuania in the early 20th century, they were largely uprooted by the Soviet regime. Therefore what exists now is mainly a heritage of the early 1990s when various missionaries came to Lithuania and converted people who were largely unused both to missionary activity and religious freedom. For instance, many people of Elektrėnai (a Soviet-built town that had no church building in the early 1990s) did not differentiate the missionaries of the New Apostle Church from the Catholic clergy.

In Vilnius there exist Mormon (LDS), New Apostle Church and Tikėjimo žodis church buildings/meetinghouses all built in the late 1990s. Main new religious movements also own churches in Kaunas, Klaipėda, and a few towns while in the rest they preach in rented halls.

Baptist and Methodist denominations own 19th-century churches in Klaipėda and Kaunas respectively but their fate was just like that of their congregations. Curbed by the Soviet Union, they were reborn only in the 1990s.

The minor Christian denominations largely drew members from those who (or whose parents) had abandoned the Christian faith as a result of Soviet atheist policies. As many such irreligious people belonged to Russian and Russophone minorities, a disproportional number of the followers of "minor Christian faiths" are now ethnic Russians and Russophones. Therefore, relatively many prayer meetings are conducted in Russian and some entire churches are Russian-speaking. The majority of such churches are, however, mostly Lithuanian.

Many minor Christian communities are partly funded by their richer counterparts in the West. "Tikėjimo žodis" is the only significant Lithuanian-originated Christian church but it has also been founded and expanded in the 1990s.

Jehovah Witnesses Lithuanian headquarters in Giraitė suburb near Kaunas. Like most buildings of the new Western faiths, it is extensive and modern yet modest in design. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Asian Faiths in Lithuania (Moonies, Krishnaism, Buddhism)

New Asian faiths like the Krishnaism or the Unification church (“Moonies”) became more popular with the reestablished religious freedom in the 1990s, although the Krishna movement made minor penetrations of Lithuania’s hippie scene in 1980s. In the 1990s, the Krishna marches across major cities were a relatively common sight but have since become less popular.

In the 2000s more people embraced the Buddhist practices or certain elements of the Hindu religion such as Yoga. These practices, however, are usually not fully understood by their adherents. The long atheism years brought Lithuania to a situation where many people could not describe what they believe in with e.g. the same person claiming both that the Christianity is right and that people reincarnate like the Buddhism claims, or that the Taoist principles are correct and eventually saying that there is no God or supernatural forces altogether. Usually, such people have never read religious texts of any faith in full and only heard certain quotations, e.g. by their Yoga teacher.

According to 2011 census, there are 620 self-reported Buddhists and 350 Krishnaites in Lithuania.

Krishnaites marching with Hare Krishna chants along the Basanavičiaus street in key Palanga seaside resort during a summer weekend. Usually, Krishnaites select the most crowded locations for their marches. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

New Eastern European faiths in Lithuania

The Soviet Union left many Lithuanians fluent in Russian and in need of certain spiritual guidance. The same situation also prevailed in the other lands of the former Soviet Union. Therefore, the ideas of the new prophets that appeared in Russia in the 1990s quickly spread across the former Union, gaining some adherents in Lithuania as well.

However, you won’t find these people unless you will search for them. Many of these faiths do not require any outward symbols that would distinguish people professing them from the Christians or the atheists. The exception here is the Anastasians, followers of the ideas by Vladimir Megre (and a girl called Anastasia V. Megre supposedly met in Siberian forests). These people move to the countryside where they own what they call the “family garden” or the “space of love”. This is a territory of 1 ha per each family where they grow food and Siberian pines (called “cedars” in Russian), held to be of special importance. An Anastasian community may be found in Sukiniai, Ukmergė district municipality.

Other, less visible „Post-Soviet faiths“ include the Vissarion one, claiming that a person called Vissarion who built a new village in Siberia is the second coming of Christ. Additionally, there is the New Thought-inspired Transurfing of Vadim Zeland and others.

Perhaps due to the Soviet stigma of being religious many followers of these movements deny their religiousness by claiming that what they follow is a „philosophy“, „lifestyle“, „science“ or simply „the truth“ instead. They may style themselves to be either atheists, agnostics or Christians in censae.

A modern house in Anastasian community in Sukiniai, Ukmergė district municipality (Aukštaitija region). This village is being developed deep in the countryside and is probably the largest among Anastasian communities. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

New local faiths in Lithuania (Merkinė Pyramid)

Most of the new religious ideas came from the foreign countries, however, there are a few local ones. The most famous is the New Age thought of Povilas Žėkas, the builder of triangular Merkinė Pyramid in Dzūkija National Park.

According to Žėkas, the pyramid was built after God's revelation who told Žėkas exact proportions of various metals needed for the material of such a holy building. Erected in 2002 the pyramid attracts a constant flow of people from Lithuania and abroad seeking to use its powers of healing and spiritual improvement. The pyramid complex is slowly expanded and has been covered by a glass dome in 2009 making it impressive to see even for non-believers (there are simply no comparable structures in any religion). The visitor instructions are present in English and include making several stops at three stylized wooden crosses en-route to the pyramid and then various rings inside the Pyramid itself with palms open to absorb the energy that is supposedly concentrated by the structure. The architecturally-interesting dome also houses wooden seats (all aimed at the center), three quotations, two asymmetrical metal crosses, a dispenser of energy-positive water. The pyramid may be accessed by taking a dirt side-road to Česukai while en-route from Vilnius to Druskininkai (beyond Merkinė).

Influenced by Christian and Eastern doctrines, Žėkas claims an upcoming Period of Changes which will include an extensive collapse of current economic, technological, property division and other systems and will lead to mass migration. These Changes will be induced by God because the people are not living the right way, but this won't be the End of the World. Pyramid of Merkinė will continue to hold special powers as a bastion of God and Holy Communion prepared at the pyramid will also be of extreme importance. This faith (and the Pyramid) is also called "Church of God the Father" because he claims that God is one of many, but all of them have a single Father. Another name is "Shrine of Hearts". As is the case with the Eastern European faiths it is common for believers in the healing powers of Merkinė pyramid to also follow other religions (or style themselves irreligious).

Dome-covered Merkinė pyramid and the mound that marks the location of the alleged revelation. The visitors are expected to stop at various places both before and after entering the pyramid eventually reaching its center. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Irreligiousness (Atheism) in Lithuania

Irreligious people make 6,8% of Lithuanian population. They may roughly be divided into multiple groups: rigorous followers of science, agnostics, and radical leftist atheists. This last group, disproportionally represented in media, seeks to limit the rights of the religious and promotes some scientifically disproven theories.

Beyond these groups, the religious-irreligious line is blurry at best. Some followers of religious-in-nature beliefs also style themselves irreligious, while many others associate themselves with a faith but practice it only occasionally or partially.

The key of explaining these paradoxes lies in the Soviet occupation (1940-1990). Before it (in the 1930s) virtually everybody in Lithuania followed some religion. The Soviet atheist regime, however, sought to eradicate the faith through discrimination and propaganda. "Atheism" became a subject taught in universities and even had museums dedicated to it; it was a necessity for climbing the tightly controlled career ladder. The "Soviet irreligiousness" was, however, in a sense a fundamentalist faith by itself. A "good atheist" was expected not to question any Marxist-Leninist doctrines; those who did, used to be forcibly "treated" in psychiatric wards. Radical leftist atheism of today's Lithuania, in essence, follows this tradition although European far left now replaces Soviet communism as the source of inspiration.

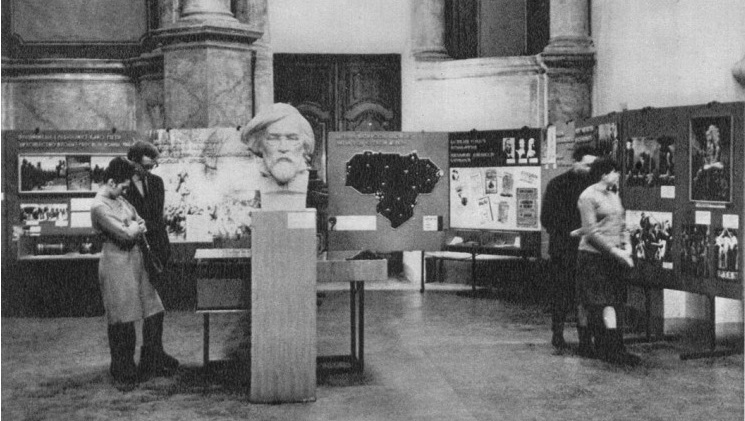

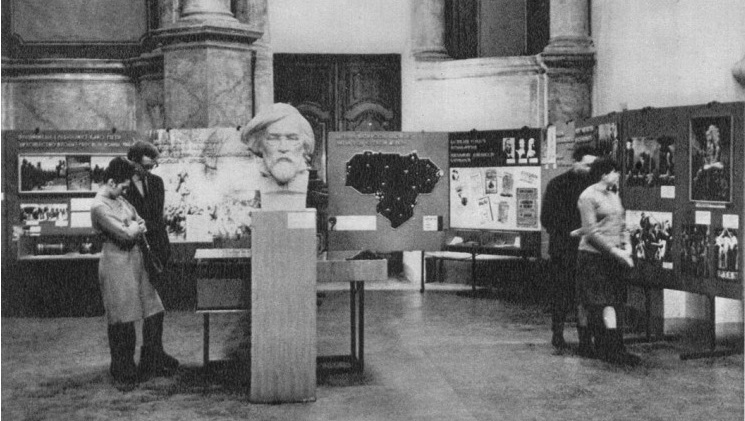

Vilnius Museum of Atheism, established by the Soviets in a nationalized St. Casimir church. After independence (1990) the state promotion of atheism ceased and the church has been reopened.

The decades of anti-religious propaganda (with e.g. extensive education on the millennium-old Crusades but none at all on the millions recently murdered in Soviet genocides) made the word "religion" itself controversial to some, so many post-Soviet religious movements (and their followers) avoid it.

The strong atheism-collaboration link made irreligiousness socially unacceptable while the Soviet occupation continued. Following Christian rites was a form of defiance. Few ethnic Lithuanians abandoned their religion but the church closures, textbook shortages, and discrimination impeded regular worship and passing the faith to children, making the Soviet-born generations less religious. Additionally, many irreligious Russian and Russophone settlers were moved in.

After independence (1990) state atheism was replaced by religious freedom. Large numbers of the irreligious re-found their forefathers' faiths or converted to new religious movements. Atheism has been especially shrinking among the Soviet settler communities where it had been the most prevalent (~26% irreligious in 2001, ~12% in 2011) but also in the population as a whole (10,5% in 2001, 6,8% in 2011). Currently, Jews are the most irreligious ethnicity (43,5%) and Poles are the least irreligious (1,7%). Northeastern Samogitia is the most irreligious region of Lithuania (~11%), followed by the main cities (8%-10%). Other municipalities have 1% to 6% non-believers.