Culture of Lithuania: Introduction

The culture of Lithuania is standing on six pillars:

The ethnicity. The old Lithuanian nation was joined by multiple minorities over the centuries, and to many their ethnicity is the prime self-identification and the main source of cherished traditions.

The language. The archaic Lithuanian language may be what defines Lithuanian people. The minorities are equally protective of their languages however.

The religion. Predominantly Catholic for centuries Lithuania was always tolerant to other faiths, which provided many alternative traditions and old houses of worship to Lithuanian towns.

The holidays. From local to universal, from meaningful to forgotten, from straightforward to controversial: every week has festivities in Lithuania, each of them dating to a different historical period or group of people.

The architecture. Formed by ethnicities and religions, foreign influences and occupations, a multitude of architectural styles define the contemporary Lithuanian villages, towns and cites.

The arts, crafts and literature. Mostly created during periods that already seem exotic in a rapidly-changing Lithuania the art, crafts, and literature are still respected as something that best conveys the development of Lithuanian culture to the present-day people.

Furthermore, read about the massive Lithuanian diaspora that keeps the Lithuanian culture alive well beyond Lithuania.

Ethnicities in Lithuania: Introduction

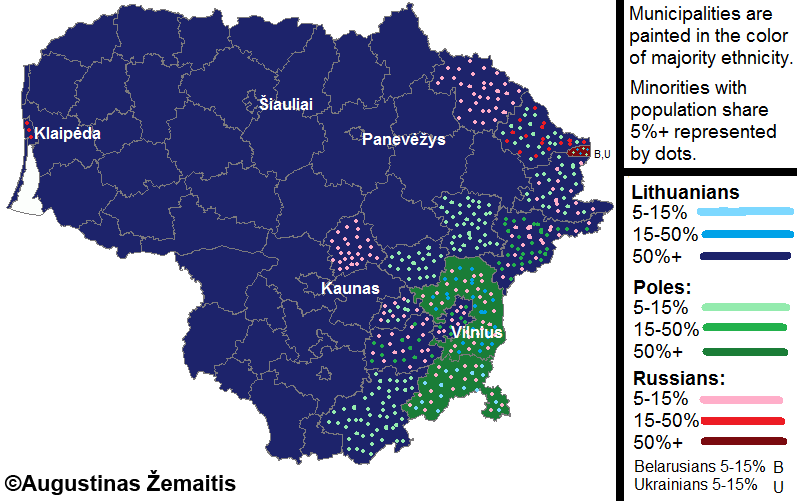

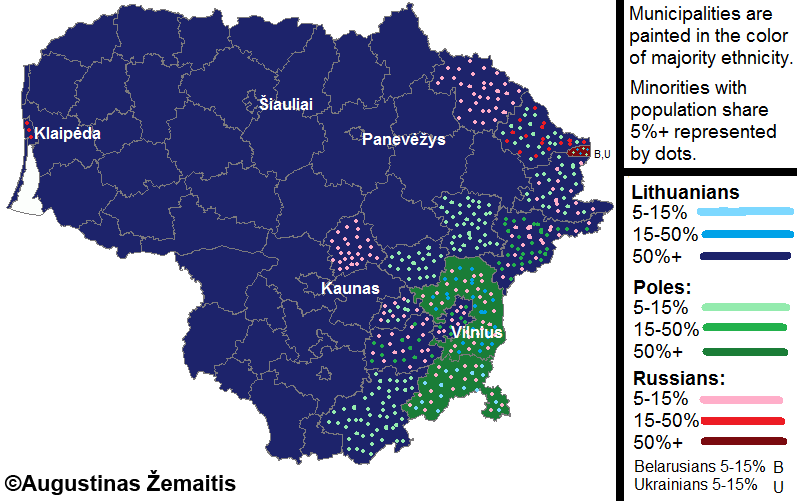

The majority ethnicity in Lithuania is Lithuanians, who make up 85,08% of the population and are the country's original inhabitants.

Poles come second (6,65%), mostly concentrated in Southeast Lithuania, including Vilnius. Russians are third at 5,88% with their liveliest communities in cities.

The fourth largest ethnicity in Lithuania was the Belarusians (1,2%), though by now they are certainly surpassed by Ukrainians (0,55% before the Russo-Ukrainian war, likely ~3% today). Together with the other ethnicities of the former Soviet Union, these two are concentrated primarily in the cities.

Other traditional minorities in Lithuania are the Jews, Germans, Tatars, Latvians, Karaims and Gypsies, each of them dating to 14th-15th centuries but consisting of 0,1% or less population today.

Inter-ethnic relations are generally good in Lithuania. Unlike in many European nations, Lithuania’s largest ethnic minorities enjoy public schools where the language of instruction is their native one rather than the official Lithuanian language. However, other points of language policy raised discussions recently, such as the legality of Polish street names in Polish-dominated municipalities.

Inter-ethnic marriages used to be shunned by peers while under the Soviet occupation (as the offspring were then likely to assimilate into the Russophone culture, threatening the long-term existence of the Lithuanian nation) but are now generally a non-issue if both spouses belong to the traditional communities.

Like elsewhere in Eastern Europe the concept of nation is more associated with ethnicity than citizenship, therefore using the term "Lithuanian" for ethnic minorities may be controversial (both among the minority in question and the rest of the population). Conversations about one's ethnicity are generally welcome.

All the traditional communities (well over 99% of the population) are White. Races are thus seen as an external issue used to describe global (rather than local) diversity.

Ethnic map of Lithuania. The minorities are largely concentrated in the east. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

See also - History of ethnic relations in Lithuania

Religion in Lithuania: An Introduction

In the globalized world of 21st century, few would be surprised by multi-religious cities. However, in Lithuania, the multi-religious atmosphere is centuries old. The 19th century Vilnius had temples of over 10 different religions, many of them non-Christian. Lithuania is a unique crossroad of the East and the West in that here you can see the centuries-old heritage of many different faiths.

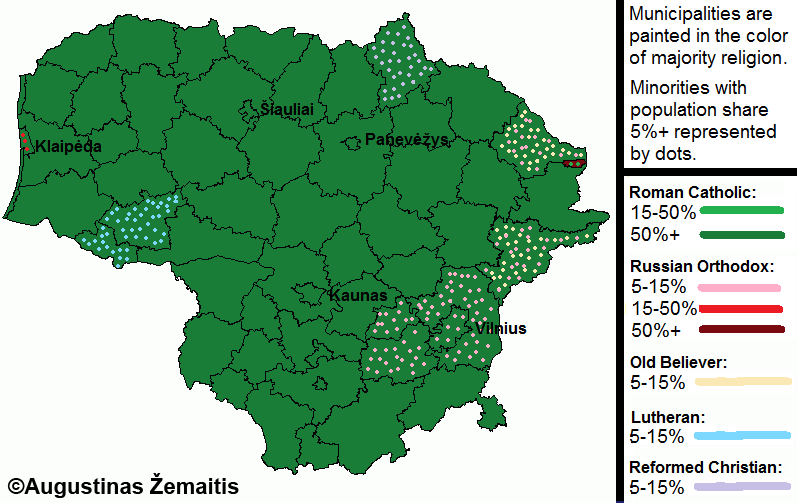

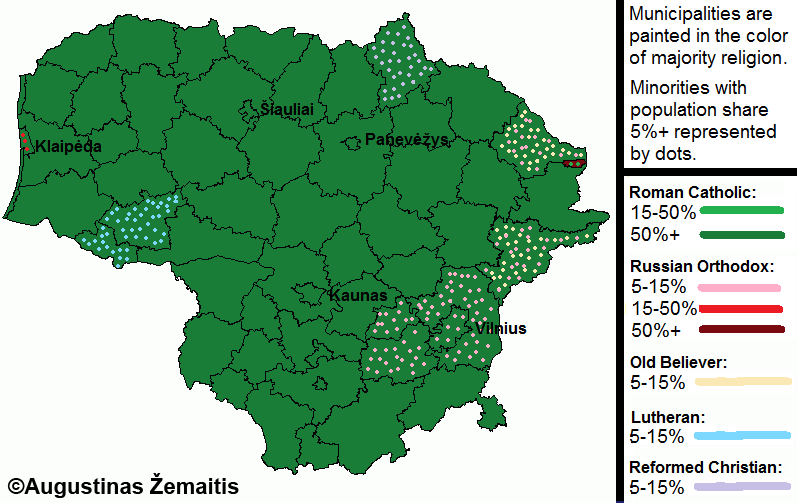

Today most (some 85,9%) Lithuanians are Roman Catholic and the interwar Lithuania was a very religious society. However the long Soviet occupation (1940-1941 and 1944-1990) with its anti-religious policy brought in a flavor of sometimes radical atheism (6,8% irreligious). It also triggered a decline in religious services attendances and a more clandestine role of religion, which is still largely invisible in public places.

The interior of a Roman Catholic Cathedral in Šiauliai city (Samogitia region). Relatively plain interiors like this are common ir newly restored churches once damaged by the Soviets and wars.

Second largest faith is the Russian Orthodoxy, followed by 4,6%, mostly ethnic Russians. 0,9% of the population are Old Believers, whose Russian ancestors received refuge in Lithuania when they were persecuted in Russia for refusing to adhere to the Nikon’s religious reform. Lutherans, 4th largest religion (0,7%), enjoy a centuries-old stronghold in Klaipėda Region, while the Lithuanian center of the Reformed Christianity (0,2%) is the Biržai district in the northeast.

Four other faiths are considered traditional by the Lithuanian law, and they are:

*Sunni Islam, adhered by Tatars whose ancestors were brought as soldiers to these areas by Vytautas the Great.

*Judaism, the religion of the Jewish community, severely weakened by the Nazi Germany's Holocaust, Soviet atheism and the emigration to Israel.

*Karaism, an old offshoot of Judaism practiced mostly in Vilnius and Trakai.

*Uniate Christianity (Eastern Catholicism), a form of Christianity whose devotees recognize the Pope as an authority but follow the Eastern orthodox liturgy.

Each of these faiths is now followed by 0,1% or less population but their centuries-old communities are important for Lithuania’s history and culture.

Since independence, the number of adherents of new or foreign religious movements increased but they all put together remain under 1%. 0,5% belong to minor Christian faiths and 0,2% are neo-pagans.

Lithuania recognizes religious freedom. Traditional religious institutions are treated like any cultural institutions. The state could support them (but such support should be proportional to the number of their followers).

Map of Lithuanian religious communities. In most municipalities, 90%+ people are Roman Catholic. Significant religious minorities are concentrated in particular areas. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Languages in Lithuania

The sole official language in Lithuania, as well as the language you will hear the most, is Lithuanian (native to some 85% of the population and spoken by 96%). With millennia-old history and struggles for its survival, Lithuanian language is very much a part of national identity.

Minority languages in Lithuania

The largest minority languages are Russian and Polish, spoken natively by 8,2% and 5,8% of the population respectively.

Russian native speakers live primarily in cities. They include not only ethnic Russians but also many Belarusians, Ukrainians, Jews and other ethnicities common in the former Soviet Union, collectively referred to as Russophones. Some "Russophones" speak another language natively but still speak better Russian than Lithuanian or don't speak Lithuanian at all. Not speaking Lithuanian is common among the elder generation of Russophones. That's because during the Soviet occupation (1940-1990) knowledge of Lithuanian was not required and Russian was the lingua franca (unlike Latvia or Estonia, Lithuania gave its citizenship to every person who resided in Lithuania at the time of the collapse of the USSR, regardless of their knowledge of the official language).

Polish is spoken mostly by the ethnic Polish minority in the southeast Lithuania (including Vilnius). In some towns there Polish is actually the majority language.

While there are other minorities in Lithuania it is very rare to hear any other language than Lithuanian, Russian or Polish spoken in Lithuania by locals in their own conversations (rather than when talking to foreigners).

Minority languages are used extensively by the minorities in question and this is promoted by the government. For instance, there are many public schools where either Russian or Polish are used as the medium of instruction. However, any official government texts (e.g. laws or street names) are Lithuanian-only.

Christmas greetings projected under Vilnius castle tower alternates Lithuanian, English, Polish and Russian languages. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Foreign languages in Lithuania

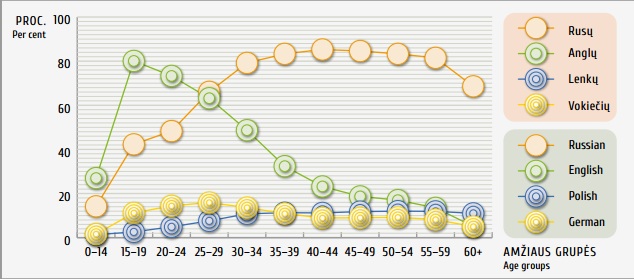

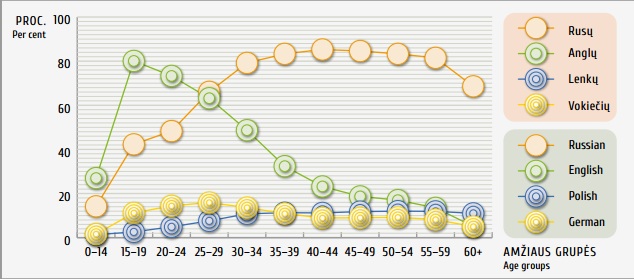

Spoken by some 70% of the population, Russian is still the most popular second language in Lithuania, although this is declining. The Russian language was both mandatory and ubiquitous during the Soviet occupation (1940-1990), making virtually everybody in the older generations (i.e. those born ~1980 and before) fluent in it. Nowadays, however, many ethnic Lithuanians regard the Russian language as a "colonial leftover". Only some 40% of the kids learn it. Likewise, Russian public inscriptions have been gradually removed or replaced by English ones (although the Russian language may still be seen on an occasional old plaque or in unrenovated museums). On the other hand, private hotels and restaurants have Russian menus and employ Russian-speakers to cater for numerous Russian tourists. While to some ethnic Lithuanians any use of Russian is a reminder of the tragic history, some others enjoy Russian music and media, claiming that "culture and politics should not be mixed".

English is the most popular foreign language to learn today. It is spoken by 30% of total population and 80% of the youth. The older generations are unlikely to speak English, however, as very few schools taught it seriously under the Soviet occupation. Today English is the language Lithuanians expect foreigners to know, so it is widely used in modern museums, hotels, tourist signs and city/resort restaurant menus. As the "top language" of the "prestigious West", it also became fashionable for some key local trademarks and popular songs.

It is relatively rare for non-Poles to learn Polish as a foreign language. It is not taught as such in schools. However, non-Polish people from areas with strong Polish presence may have some knowledge of Polish acquired in day-to-day life, making 14% of Lithuania's citizens fluent in Polish. Polish signs for tourists are available in the areas most visited by the Polish tourists, namely the Vilnius region and the borderland. Polish-inhabited areas have Polish cultural events and media, although they are mostly aimed at the local Poles.

German (spoken by 8% of the population) held popularity as a 2nd foreign language (after Russian, instead of English) under the Soviet occupation as the Soviet Union had close ties to East Germany (but no close ties to any English-speaking country). Today German usually competes with Russian for the place of second foreign language in school (after English). In the formerly German-ruled Klaipėda region, restaurant menus and other information in German are more common due to catering for numerous German tourists there. In terms of cultural impact, German is far behind English, Russian and Polish, however: there is no local German media, few cultural events, few books for sale and so on.

Fifth and sixth foreign languages by the number of speakers in Lithuania are French and Spanish, but they are spoken only by some 2% and 1% of the population respectively.

2011 census results on the correlation between age and what foreign languages a person can speak. Native languages are excluded (therefore total numbers of Russian and Polish speakers are larger by 6%-8%). Diagram by Lithuanian department of statistics.

Lithuanian diaspora

Lithuanians are among the nations that have emigrated the most. Some 2-3 million people may have left Lithuania in the past two centuries, almost as many as there are inhabitants in Lithuania today. Due to intermarriages, some 6 million people worldwide may have at least a single great-great-grandparent from Lithuania by now.

This Lithuanian diaspora did not simply dissipate: it has built massive churches and club palaces, established century-lasting organizations and traditions, and, essentially, became "the other Lithuania" that had to be reckoned with, constantly replenished by new and new waves of emigration. Many of the key Lithuanian feats were achieved by the diaspora, such as publishing the first Lithuanian-language novel or encyclopedia.

Lithuania's sad history of occupations and persecutions is responsible for much of the emigration, but there were numerous waves and groups of emigrants that had different reasons, goals, and life after emigration. Whether you are a descendent of a Lithuanian emigrant or you seek to understand Lithuania and Lithuanians more these articles will help to learn all the whys and hows.

Numbers and locations of Lithuanian diaspora

Few estimations vary as wildly as those of Lithuanian diaspora numbers. That's because there is no clear definition of who is a Lithuanian and different countries use wildly different measures for statistics, including citizenship, birthplace, native language, ancestry, self-declared identity, etc.

Lithuanian diaspora is easiest to understand as a series of Migration Waves. The members of the same Migration Wave and their descendants have more in common with each other (even if living oceans apart) than they do have in common with the Lithuanians from other waves (even if they migrated to the same city). The Waves are described in the paragraph after this one.

The following liberal geographic estimates include people who are either ethnic Lithuanians, descendants of ethnic Lithuanians with exposure to Lithuanian culture, or Lithuanian citizens, irrespective of their language knowledge, place of birth or diaspora participation. They do not include non-Lithuanians who temporarily resided in Lithuania (e.g. during the Soviet occupation) and then emigrated. With limited data for some countries, some of the estimates still have a big margin of error.

A map of Lithuanian diaspora, each square Lithuanian flag representing 50 000 diaspora members and each smaller flag 10 000

Click on the country names on the table to learn more about Lithuanian heritage there.

| Country | Number of Lithuanians | Comments |

| United States | 650 000 | Mostly First wave (pre-1915) and Second wave (~1940s). Mostly New England, Mid-Atlantic and Midwest. |

| United Kingdom | 200 000 | Mostly Third wave (post 1990-). Mostly cities. |

| Brazil | 60 000 | Mostly interwar migrants (1920s). Mostly Sao Paulo. |

| Germany | 55 000 | Mostly Third wave (post-1990) |

| Norway | 50 000 | Third wave only (post-2004) |

| Canada | 47 000 | Mostly Second wave (~1940s). Mostly Ontario and Montreal. |

| Argentina | 45 000 | Mostly interwar migrants (1920s). Mostly Buenos Aires, Beriso, Rosario |

| Ireland | 40 000 | Third wave only (post-1990) |

| Russia | 32 000 | Mostly Exiles (1940-1953), Soviet-era migrants (1945-1990) |

| Latvia | 30 000 | Mostly indigenous communities (near the Lithuanian border), Soviet-era migrants (1945-1990) |

| Belarus | 30 000 | Mostly indigenous communities near Lithuanian border, Soviet-era migrants (1945-1990). |

| Spain | 30 000 | Third wave only (post-1990) |

| Denmark | 20 000 | Third wave only (post-2004) |

| Sweden | 16 000 | Third wave only (post-2004) |

| Poland | 15 000 | Mostly indigenous communities near the Lithuanian border |

| Australia | 13 000 | Mostly Second wave (~1940s). Mostly Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Canberra, Geelong, Perth. |

| Uruguay | 10 000 | Mostly interwar migrants (1920s). Mostly Montevideo. |

| Kazakhstan | 7 000 | Mostly Exiles (1940-1953) and Soviet-era migrants (1945-1990). Mostly Karaganda. |

| Ukraine | 7 000 | Soviet era migrants (1945-1990) and Third wave |

| The Netherlands | 7 000 | Third wave only (post-2004) |

The Lithuanian emigration waves

Lithuania's emigration waves were so different from each other that they are the most important groupings of Lithuanian emigrants.

Destinations, periods, ethnicities, professions greatly depend(ed) on the wave with which the person has left Lithuania.

*Indigenous Lithuanians abroad. This part of the Lithuanian diaspora has never emigrated: they live in the same Lithuanian areas and villages their families lived for centuries and millenniums. However, 20th-century politics meant that these villages were not included in the Republic of Lithuania, being awarded to Russia, Poland, Belarus, or Latvia instead.

*Pre-modern emigration (before 1865). Before mid-19th century, migration was only accessible to Lithuania's elite. They left to rule far-away lands of Grand Duchy of Lithuania, left for international noble marriages, missionary duties, or escaped political enemies - yet they were so few in numbers they quickly assimilated in the regions they went to (or assimilated into the local Polish or German communities). Sometimes they left traces in stones - but little traces in local culture.

*First wave (1865-1915). A.k.a. "Grynoriai". At the time Lithuania was ruled by the Russian Empire which enacted discriminatory policies, was economically backward and left Lithuania undeveloped on purpose. Avoiding discrimination and seeking economic opportunities Lithuanians (mostly peasants) thus emigrated in larger numbers than ever before with some 700 000 leaving, most of them to the USA where they would work in the industry and mines. They established entire "colonies" abroad that included Lithuanian churches, club palaces, businesses. Lithuanian language and culture lingered for over a century in some of them, and the heritage still remains in many more.

*Interwar Lithuania emigration (1915-1939). While 1918 Lithuanian independence quenched the anti-Lithuanian discrimination back home and kick-started the economy, Lithuania still had a lot to catch up. Some Lithuanians (~100 000) did not wait and emigrated instead: as the USA was by then effectively closed to immigration, most have chosen South America or Canada, creating smaller versions of "First wave" Lithuanian "colonies" there. This minor wave of emigration was cut short by the 1929 Great Depression that ravaged the western economy more than that of Lithuania. Furthermore, during this period many of the pre-1915 Russian Imperial settlers emigrated to their own countries.

*The Exiles (1940-1953). Considered to be the most tragic part of recent Lithuanian history, they were a part of genocide. Soviets expelled some 350 000 to Russia's most inhospitable lands. Many of them died due to forced labor, malnutrition, and cold, leaving little trace behind them. A smaller number was also expelled to concentration camps by Nazi Germany in the 1941-1944 period.

*Second wave (~1944). A.k.a. "DPs", "Displaced persons", "WW2 refugees", "Soviet Genocide refugees". As Soviet armies invaded in 1944, many Lithuanians knew they were targets of the Soviet Genocide and so fled for their lives, mostly westwards. After several years spent in refugee camps, they would spread across key Western nations (mainly the USA, Canada, and Australia). Numbering at 70 000, the Second Wave was smaller in numbers than the First Wave, it left as big a mark on Lithuanian history because many second-wavers were patriots who would have never left Lithuania in other circumstances, so they worked hard to recreate a piece of Lithuania in their new homelands, keeping the Lithuanian language and culture alive and vehemently campaigning for Lithuania's freedom. Many of them were also intellectuals, launching the Lithuanian-styled arts, architecture, and sciences abroad.

Lithuanians DPs in a ship which moves them from refugee camps in Germany to a new world (left image). They later established cohesive communities, such as the one centered around this new (1950s) Nativity BVM church in Marquette Park, Chicago (right image).

*Emigration from Soviet Lithuania (1945-1990). Emigration from the Soviet Union was nearly banned, making the number of emigrants low despite some of the most horrible living conditions in Lithuanian history. Non-ethnic-Lithuanians, however, were often allowed to emigrate to their titular homelands and some 250 000 of them did (most of Lithuania's Jews emigrated to Israel, many Poles to Poland and Germans to Germany). There were also movie-scenario-like stories of escapes and infiltrations. Emigration to other parts of the Soviet Union was allowed (sometimes even encouraged) for all ethnicities, however, few Lithuanians wanted it.

*Modern emigration or the Third wave (1990-). The current and largest wave of Lithuanian emigration. As European Union membership allowed free and uncontrolled emigration to Western Europe, almost a million Lithuanians (over a quarter of the total population) used up the opportunity to leave their Soviet-ravaged homeland for larger salaries of the West. Most of them settled in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Norway, Spain, and Germany. Furthermore, many of the Soviet settlers departed for their historic homelands.

Note: this classification into three waves is the prevalent one in Lithuanian historiography and Lithuanian words such as "antrabangiai", "trečiabangiai" (second-waver, third-waver) are understood in the diaspora. There are alternative classifications, however, e.g. one with five waves, considering Interwar and Soviet migrations as separate waves. However, these migrations are more correctly seen as low-points of emigration from Lithuania between the "waves" (high-points).

Architecture in Lithuania: Introduction

For centuries Lithuania was known as a land of endless lush forests, interrupted only by rivers. As such, the traditional architecture in Lithuania is wooden. In most smaller towns, almost every building that had been constructed before the 20th century is built of wood. Wooden churches (both Catholic and Orthodox) are common in villages, there are even wooden mosques and synagogues. Some of the wooden buildings are very elaborate and with intricate details.

In the downtowns of the main cities, however, the brick started to displace the wood as early as in the 14th century. Romanesque architecture was the first international style to reach Lithuania but few examples of it survive. Some of the most famous architectural gems date to the Gothic period (such as the Saint Anne’s Church in Vilnius) and subsequent Renaissance. This period was followed by the Baroque that is the best represented in the church architecture of Vilnius. Only a few cities have brick pre-19th-century districts, however: Vilnius, Kaunas, and Kėdainiai are the best-known examples.

Saint Casimir Baroque church in Vilnius. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

In the late 18th century, the Neo-Classical architecture came to Lithuania, emulating the Roman Empire style. In the mid 19th century, it was displaced by historicism that copied various earlier styles and sometimes a combination of thereof. This period gave many large buildings to the cities (apartments and public buildings) while many smaller towns received their neo-gothic church spires that now dominate the Lithuanian landscape (Roman Catholic faith became free to practice and expand in the Russian-controlled Lithuania only after 1904). Neo-Romanesque, Neo-Renaissance, and eclectic historicism styles were less common for these churches.

Another major part of architectural heritage of pre-20th century Lithuania are the manors in the countryside as well as in the cities and towns (where they are typically surrounded by well-crafted parks) that used to be owned by the noble families like counts Tiškevičiai or dukes Oginskiai. Their architecture follows the popular styles of the period, with the manors of poorer families built of wood. In the case of many towns, the manors were not only their part but actually their heart, because the towns were considered to be a property of the local nobles.

Meticulously repaired palace of the Plungė manor (Plungė, Samogitia). It was built in 1879 by the duke Oginskiai family in historicist style. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

After the World War 1, Kaunas became the temporary capital of Lithuania, therefore, it expanded rapidly and received many fine art deco buildings. However, the main period of urbanization came under the Soviet occupation (in 1939 70% of Lithuanian people lived in villages; in 1989 70% of Lithuanian people lived in cities). Initially this meant construction of buildings in a style known as Soviet historicism, but as early as 1954 all “unnecessary architectural details” were cancelled and every new building had to be built in a blunt functionalism style, making all the new districts that surrounded every city very faceless and hard to distinguish from any other city in the Soviet Union (in a popular Russian comedy “After bath” a drunk man goes to Saint Petersburg instead of Moscow and does not realize this because of similar district names, street names and buildings). In the villages, many old wooden houses were replaced by similar looking prefab “Alytus homes”. Shops, schools, and hospitals also used to be built by similar designs all across the Union.

Pienocentras HQ in Kaunas (1934) is an example of interwar architecture that combined sharp corners and curved lines. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The post-independence (1990) era brought glass-covered buildings and skyscrapers to the major cities, especially Vilnius and Klaipėda, but the expansion in smaller towns and villages remained more modest. Around the major cities, new suburbs of private homes appeared out of nowhere. The first such houses after the restoration of the private property used to be big, with castle-like features as the families built them for generations to come (unfortunately, changing fortunes or too large wishes meant that some of these buildings are still incomplete). In the 2000s such “manors of the 20th century” gave way to smaller western-style detached homes.

Holidays in Lithuania: Introduction

15 annual public holidays puts Lithuania in the top ten of countries that have the most public holidays. Coupled with 28 days of mandatory paid annual leave Lithuanians indeed have time to celebrate. While the centuries-old traditions were hit by various occupations and cultural persecutions of the 19th-20th centuries, many have survived, some others are reintroduced or started anew.

Types of Lithuanian festivals

Being a Christian country Lithuania has traditional Roman Catholic holidays as its most widely celebrated annual events. This includes Easter, Christmas and, more uniquely, Christmas Eve. The Day of the Dead lacks the flash of its Mexican version but is nevertheless celebrated in a unique way as the Day of the Souls. The Christian holidays are typically family events and as such are celebrated by religious and non-religious alike.

In Christmas period, the city square where the main Christmas tree stands becomes the focal point for outdoor activities. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Being Europe's area where paganism remained strong for the longest time, some of the traditional Lithuanian holidays, while primarily Christian, have surviving pagan influences. There have been attempts to reinstate some pagan or paganism-inspired events that have already died out. Saint John's Eve (Joninės or Rasos) is among such holidays.

Lithuania has little traditions in celebrating its national (patriotic) holidays, of which it has many. Sombre official events take place, but the days are not observed by the majority of the population. New celebration ideas, sometimes readily accepted, sometimes meeting opposition, arose in the recent years and they include parades and mass singing of the national anthem by Lithuanian communities worldwide.

Lithuania also has an array of holidays celebrated by specific groups: students and teachers, lovers, women, workers, Russians. Some of these festivals are universally popular, others are derided by many for their Soviet origins (or, less commonly, ignored by some for being "unnecessary new imports from the West").

Lithuanian flags must be waving at every building during the February 16th, March 11th and July 6th patriotic holidays. During the other holidays (religious, ethnic, group), the flags are optional. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Lithuanian cities established their own annual events - generally, the larger is the city, the more there are local events. Minor towns have their own holidays coinciding with the days of the saint to whom the local church is dedicated. While religious in nature those days include secular events such as a market, a concert, reunions of families descended from the area and so on.

Each Lithuanian person and family also has personal celebrations of lifetime events. This includes weddings, birthdays, funerals and childhood/teenager "initiation rites" originating in both Christian and secular educational traditions.

Public holidays in Lithuania

The public holidays in Lithuania are:

January 1st - New Year (also the National flag day)

February 16th - Day of State Restoration

March 11th - Day of Independence Restoration

Date set by the Roman Catholic tradition - Velykos (Easter Sunday)

Date set by the Roman Catholic tradition - Velykos (Easter Monday)

May 1st - Labour day

First Sunday of May - Mother's day

First Sunday of June - Father's day

June 24th - Joninės / Rasos (St. John's day)

July 6th - State day (Day of King Mindaugas coronation)

August 15th - Žolinė / Virgin Mary Assumption day

November 1st - All Saints day

December 24th - Kūčios (Christmas Eve)

December 25th - Kalėdos (First day of Christmas)

December 26th - Kalėdos (Second day of Christmas)

Traditional holidays that are not public holidays but are nevertheless eagerly celebrated include Užgavėnės (Carnival). Usually, the main public celebrations of such events are done in the weekend.

Many traditional ethnic Lithuanian holidays, such as Joninės (pictured) and Užgavėnės, puts an emphasis on clothing. Folk costumes are prefered, appended by holiday-specific items (wreaths for Joninės, masks for Užgavėnės). While few people actually dress this way today, they still are visible during the particular days. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Most shops and restaurants are open during the holidays although there may be some alterations during the major celebrations (Easter, Christmas and New Year).